Cinematic Universes Aren't New; They're the Oldest Stories on Earth (Marveliad: Eps. I + II)

EPISODE I: THERE WAS AN IDEA

The rationale behind Hollywood’s present-day focus on sequels, franchises, blockbusters and IP is well understood. These titles are most likely to generate $100MM+ profits, sprout even more money-making spinoffs, and transition into a myriad of ancillary revenue lines, whether it’s a theme park ride, pair of pajamas, or Coca-Cola branded partnership.

But more important than the opportunities for revenues is the simple fact that audiences love these films. And the films they love most of all share a lot in common: they tell expansive tales with numerous fantasy and/or science fiction elements, feature existential threats that span, if not planet Earth, the entire universe, and boast enormous casts. By 2019, these films have become so popular it’s nearly impossible for any other sort of film to succeed at the box office.

Why are these movies so big? While Hollywood is in the business of actively marketing its content, we aren’t being forced to love them. The major studios don’t ultimately care which genres we prefer. They would be just as happy to build universes around less fantastical series like Die Hard, The Godfather, or Fast & The Furious. There must be something very fundamental about our appreciation for stories like Star Wars, the Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter… and of course, the Marvel Cinematic Universe. For all their fictions, absurdities and CGI, they must be uniquely capable of connecting with a massive audience.

And this is easy to see.

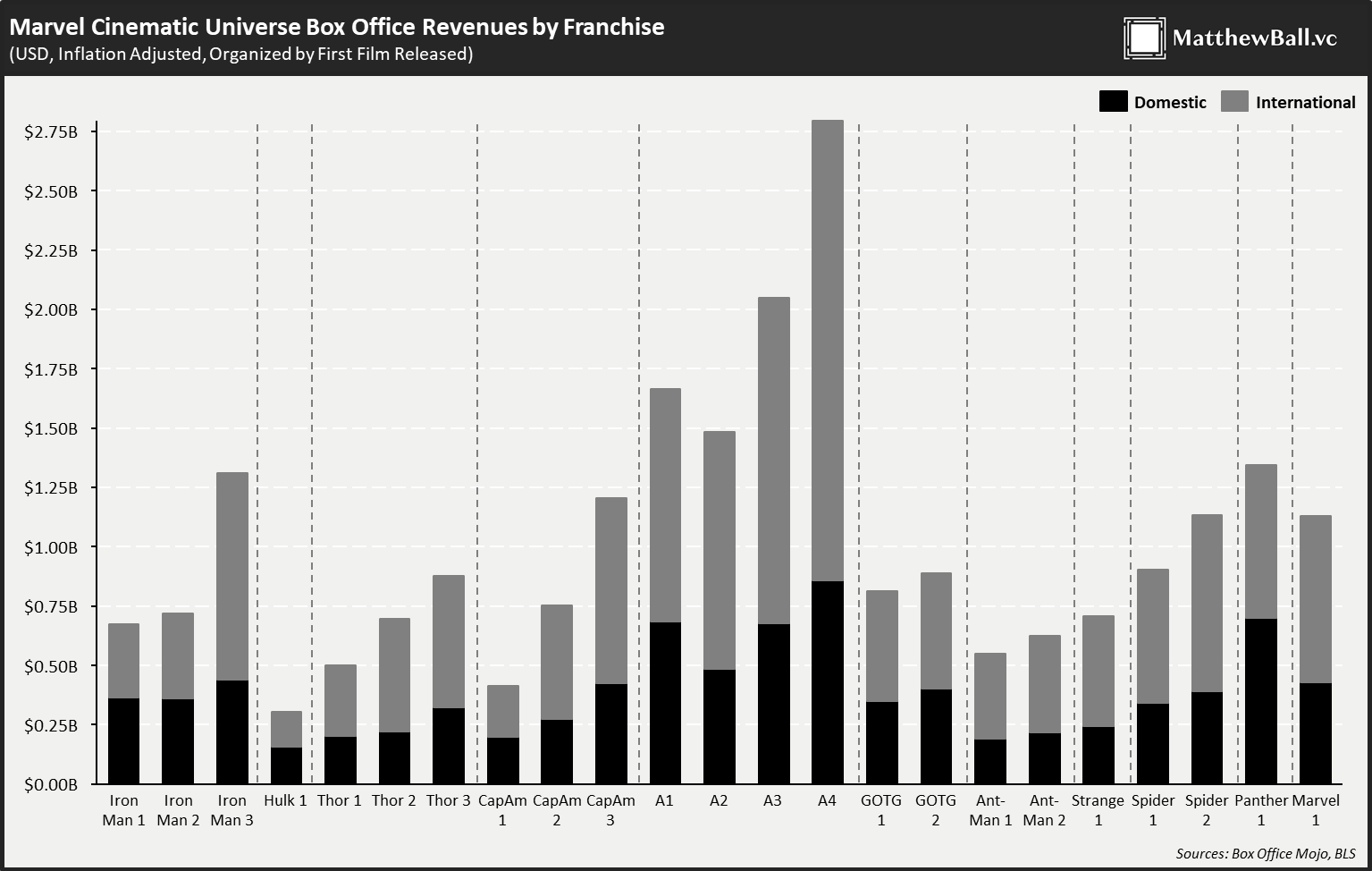

Over its first five years (“Phase 1”), the Marvel Cinematic Universe released an average of 1.2 films per year and grossed $291MM (inflation adjusted) per film domestically. Since 2016 (“Phase 3”), the MCU has released 2.75 films per year and averaged $450MM per film. And only two of these 11 films grossed less than the Phase 1 average. To date, the MCU has released a total of 12 sequels across its sub-franchises like Iron Man, Ant-Man and The Avengers. Theses sequels out-grossed their predecessor by an average of 31%, with only one grossing less. And the one film that declined was the second Avengers film, which was the sequel to the third highest-grossing film of all time and still went on to become the sixth highest-grossing film in history.

The brand equity built by the MCU has not only grown the value of well-known IP, such as Captain America and Spider-Man, but enabled the creation of brand-new blockbuster IP that had no pre-existing popularity, let alone affinity. The Guardians of the Galaxy comic book and characters were essentially unknown when the movie was greenlit. It starred a walking tree that can say only three words, a sentient cybernetic raccoon, a scarified purple alien incapable of sarcasm, a second scarified alien (this one green) with a half-machine sister (who is blue), and one human character with no superpowers. Despite this, the film went on to become the third biggest film of the year, and its sequel ranked fifth. 2018’s Black Panther, based on another largely unknown superhero, became the fourth highest-grossing film in US history, as well as the biggest film to ever star and be directed by a person of color. It earned a Best Picture nomination, and spawned countless thinkpieces on American slavery, reparations, and isolationism. This, if nothing else, is proof of cultural impact.

Given the extraordinary success of the MCU, it’s worth pausing to consider the roots of the ‘Cinematic Universe’ as a format. While the term is new, as is its use in modern film, the origins are ancient. It is the contemporary version of our most enduring form of story.

EPISODE II: I LOVE YOU 3,000 (YEARS AGO)

For most of human history, the narrative form par excellence was the oral epic. These were the spoken sagas of Gods, heroes and monsters that our ancestors told each other as they gathered around fires and stared up at an incomprehensible universe.

Examples include the Epic of Gilgamesh, Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, the Mahabharata and Ramayana, Old English’s Beowulf, Norse Mythology, even the Hebrew scriptures. Though these tales arose in nearly every human culture, geography and age, they share many common elements. So many that some anthropologists believe they originated from a handful of stories. Regardless, their ubiquity speaks to their fundamental appeal.

These epics told stories of Gods, demi-gods and men that lasted generations and included trips across various realms, even to Heaven and Hell. Every narrative was part of a much larger meta-story, typically a dynastic war or quest. Thematically, the epic explored and reinforced virtues, most importantly, duty to family, ruler and nation. Enormous attention was paid to the particulars of these relationships and connections. There were extensive family trees that touched every character through bloodlines, conflict, or communion. No character was an isolated individual. No story was unrelated. Everyone and everything was understood within a shared context.

While these epics were often attributed to a single (probably mythical) storyteller, like Homer and Vyasa, they were actually authored by countless individual storytellers. Each imparted their own spin as they recited. Sometimes this was stylistic. In other instances, they ‘imported’ concepts from a nearby culture, or added storylines that would deliver a moral lesson or explain a real-life event, like a flood. And given most of these stories were considered the real history of the tribe, they, like history, could never end.

This process was Darwinian. Each epic was constantly being added to and remixed until the most resonant version became canon. Many epics grew so large that they could only be properly performed by specialized practitioners, who used verse and song to remember them. The Mahabharata, for example, has nearly two million words across 200,000 lines of verse. Nonetheless, the average person could probably name dozens of their favorite characters, their attributes, and deeds. The epic scope meant that there was a role model or plot line for everyone, no matter their education, intelligence or experiences.

Once classical civilization achieved literacy, it was possible for a definitive version of a story to be recorded by a single author or small group of scribes. This enabled the story to be shaped for more deliberate purposes. The Torah was canonized to explain the centrality of the Temple cult and commandments. Hesiod’s Theogony depicted how the Greek world had devolved to his present day. Virgil’s Aeneid legitimized the reign of the first Roman Emperor, Augustus, by extending and emulating the Iliad. Medieval romances promoted chivalry through mythologies of Alexander the Great, the quests of King Arthur and the wars of Charlemagne and Roland. Dante’s Divine Comedy visualized 14th century morality as a journey through Heaven, Purgatory and Hell. These authors understood that the best way to deliver a message to the masses was through an epic.

At the core of our current fascination with the MCU or the Star Wars Galaxy is a fascinating fact: they resemble the epic stories that dominated human culture for thousands of years. They tell stories that feature countless characters, each one serving a role as part of an vast story, authored by scores of unknown writers and slowly shaped by audiences, each of whom could explain - if not detail - the particulars of these universes. Even one of the most cynically criticized aspects of today’s mega-franchises is consistent with the epic model: the idea that they may never end. The MCU in particular seems to reflect this aspect of epics. Kevin Feige, the head of Marvel Studios, has said in leaked emails that he would not “in a million years” reboot characters like Iron Man. To him, Tony's story happened. It can't be unwound or redone, only built upon. That shows a keen understanding of how an epic tale lives in society. Fans are not just entertained by epics, they absorb them.

The scale and scope of the MCU’s story feels unprecedented. Yet its main innovation is not narrative - it’s that it’s told via film, rather than voice, or text, and that it’s readily understood as fiction, not history. But if the rise of cinematic universes reflects our fundamental desire for the epic form, why did they ever go away?

For the answer, see the next entry in “The Marveliad": The Disappearance, Return and Dominance of the Epic (Marveliad: Eps. III, IV + V)

Matthew Ball & Jonathan Glick