What Is an Entertainment Company in 2021 and Why Does the Answer Matter?

In the 1960s, Theodore Levitt, a resident economist and professor at Harvard Business School unveiled his theory of “marketing myopia”. Specifically, he postulated that too many companies define themselves through their products rather than the need(s) they fulfill (this idea has been largely remixed as “job to be done” theory). This mindset exposes these companies to displacement and disruption. The classic example here is the petroleum industry, which, in its obsession with fossil fuels, has missed out on solar, nuclear, geothermal, etc. Another focuses on the major railway companies of the early 20th century, which missed out on buses, cars, and trucking due to their focus on trains not transportation.

Management theories go in and out. The 1990s were particularly harsh on conglomerates, most of which struggled to show the benefits of strategy creep. Synergies sounded good and marketing myopia bad, but ultimately, most blue-chip companies delivered greater shareholder returns through focus rather than tackling uncertain (if occasionally insurgent) adjacencies. The digital era has made conglomerization a little more popular (e.g. Amazon), yet for the most part, market leaders tend to be specialized (e.g. Facebook not Google+, Shopify and Stripe not Amazon Pay, TikTok not Instagram, Tinder not Facebook Dating).

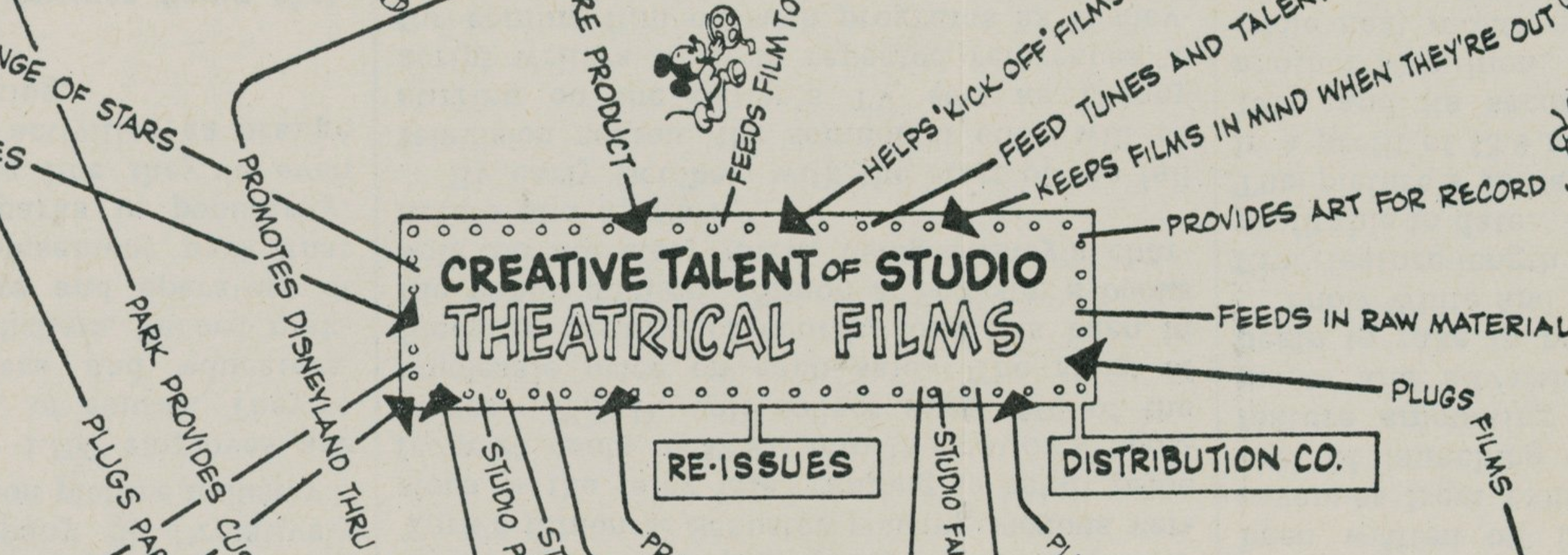

These ideas are interesting when one considers the modern-day entertainment industry. Historically, we defined an entertainment company around its core offering. Marvel was a comic book company, Mattel a toy company, ESPN a sports network, etc. When people think of the classic Disney flywheel — which Walt himself devised in the 1950s and which is the current obsession of every Hollywood executive today — they typically misremember the center of this flywheel as “IP”. It was actually “Creative Talent of Studio / Theatrical Films”. Even Walt described Disney as a movie company.

It’s clear today that these company definitions are no longer right. Disney’s theatrically-focused film studio is inarguably the best in the world (it had roughly twice the revenue and three times the margin of the #2 player in 2019). However, Disney’s parks division generated more than twice the revenue and profit of its studio division. Disney’s future, meanwhile, depends on a direct-to-consumer video platform that’s mostly growing through television series not feature films.

In 2019, Hasbro bought eOne so that it could sustain, if not build, its merchandise lines such as G.I. Joe, Transformers and Battleship into an ever-growing cinematic universe spanning TV and film. Mattel, too, is driving adaptations of its top franchises, including Barbie, Hot Wheels, and Magic 8-Ball. Most major sports leagues now see NFTs and sports betting as the key to their growth, while casinos are building out and acquiring lifestyle content publishing businesses. Marvel and DC haven’t been comic book-first companies for nearly thirty years.

And after years of dodging the question “is Netflix a tech or media company?”, Netflix founder and Co-CEO Reed Hastings recently declared, “we’re really an entertainment company”. So, what is that, why does it matter, and what’s the takeaway?

At its core, an entertainment business does only three things:

Create/tell stories

Build love for those stories

Monetize that love

A good way to learn about this is through Disney.

Disney Leads Because It’s Best at 1-2-3

Creating and Telling Stories

Sure, Disney owns many of the best stories — but it’s also best at telling them, too. Disney’s Marvel Cinematic Universe consistently outperforms the Marvel films of 21st Century Fox and Sony, as well as comic book films of Warner Bros.’ DC. Back in 2016, Sony’s film chief said, “we have deferred the creative lead [on Spider-Man] to [Disney], because they know what they’re doing.” George Lucas, who had spent decades claiming he would never sell Star Wars, has said he chose to sell Lucasfilm to Disney based on its treatment of and success with Marvel. To point, Lucas solicited no other bidders for the company — and Fox, which had distributed the Star Wars franchise for thirty-five years, didn’t even know his company was for sale. Although many argue Disney “has all the IP”, the fan response to Disney’s Marvel films versus those of Sony and Fox is in stark contrast. As is the fact that millions of fans are happy Disney finally has Fantastic Four and the X-Men “so that they can do it right”.

The last two Harry Potter films were the lowest performing in the Wizarding World’s ten films, even though the global box office has grown 150% since the franchise’s first release. There have been dozens of attempts from a dozen studios to adapt classic out-of-copyright Western tales over the past two decades (e.g. a Tarzan, two Robin Hoods, two King Arthurs, three Draculas, two Little Red Riding Hoods, three Snow Whites, a half dozen Greco and Egyptian epics, two Jungle Books, two Hercules, A Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde). At best, these films broke even. Most lost a lot. It’s hard to argue Disney would not have had greater success. And we’ll soon find out! Disney is currently working on live action adaptations of Peter Pan, Robin Hood, and The Little Mermaid. While IP matters, execution determines profit/loss.

Building Love

Disney is also best at developing love for IP. Here, the Marvel Cinematic Universe is a great example. In part because Marvel couldn’t launch its CU using its most popular comic book characters (which competitors like Sony owned), the first few films were relatively modest performers. Yet as brand equity was built, average performance soared even as output nearly tripled. Over its first five years (“Phase 1”), the Marvel Cinematic Universe released an average of 1.2 films per year and grossed $291MM (inflation adjusted) per film domestically. Since 2016 (“Phase 3”), the MCU has released 2.75 films per year and averaged $450MM per film. To date, the MCU has released a total of 12 sequels. On average, these titles out-grossed their predecessor by 31%, with only one grossing less. And the one film that declined was the second Avengers film, which was the sequel to the third highest-grossing film of all time and still went on to become the sixth highest-grossing film in history. The third Captain America came out five years after the first and grossed 2.5x.

Disney also leads in sustaining/transitioning love generationally. Consider, for example, how many families have Disneyland photos of their kids with Mickey or Woody on the fridge. Or how many of these kids have kept those photos decades later — and now as adults, they recreate the moment with their kids or compare their photo to that of their spouse.

As I wrote in “Disney, IP, and "Returns to Marginal Affinity", love is incredibly important in storytelling. It is the intangible, yet most important differentiator:

“Businesses based around storytelling franchises excel based on an intangible sort of operating leverage. Because it doesn’t actually ‘cost more’ to make someone ‘love your content more’, but the ‘value of this love’ is substantial, companies like Disney benefit from enormous “returns to marginal affinity”.

We see this in a number of ways. For example, the correlation between a film’s CinemaScore and its “multiple”. A film’s “multiple” refers to its lifetime gross divided by its opening weekend haul, while CinemaScore reflects an audience’s response to a film, and is therefore a good proxy for a film’s word-of-mouth and rewatchability. The higher a CinemaScore, the higher the multiple. Another good example of the potency of love is the ability to transfer a fan’s love for a master franchise into new spinoff blockbusters with limited history of success or awareness (e.g. the MCU launching mega-hits Guardians of the Galaxy and Black Panther). The degree to which a fan loves a franchise also informs the success of windowing — do we go to a movie in the theater, or wait until it hits home video? And for home video, do we buy, rent, or wait until it’s free on Netflix? ARPU diminishes precipitously the deeper into the window the viewership occurs.

The value of love is even stronger when applied to media products with scarcity. There’s no real cap on movie tickets or TV viewers, but Elsa dresses are finite, and theme park attendance is controlled. As a result, marginal increases in love can drive substantial pricing power. Those who need to go to Disneyland aren’t very price-sensitive, nor are parents whose daughter needs an Elsa dress. A little bit more love translates to a great deal of revenue, with no marginal cost, and substantially greater profits.

And of course, few people consume (let alone create) memes, GIFs, fan-edits, fan fiction, and theories for franchises that neither they nor anyone else loves. And these behaviors are powerful marketing and content machines (they even led to a movie being remade!). A number of Game of Thrones fans, for example, worked together to build a simulacra of King’s Landing in Minecraft. This fully immersive map, which is the size of Los Angeles, extends Westeros in a way that the series can’t and which has since reached millions. This sort of behavior is as rare as it is valuable.

Monetizing Love

Disney also has the greatest ability to monetize its love, too. Theme parks and cruises, ice shows, Broadway, retail stores, merchandise, TV, and more. No other media company has more opportunities to collect on love. In fact, theme parks are probably the world’s first hyper-optimized microtransaction game. Jungle Cruise photo here, Mickey cupcake there, click to buy a FastPass+, try on an Avengers Academy shirt inside, etc. (Update: Disney has since announced that its new Spider-Man ride will include purchase upgrades such as better web shooters, powers, and personalized gear - only Spider-lovers need apply!).

Of course, it is possible to love DC or Transformers as much as, if not more than, Marvel, even though these franchises have fewer opportunities/mediums to build fan love. However, the owners of these franchises still can’t monetize this love to an equivalent degree.

It’s equally important to note where Disney doesn’t really monetize. While The House of Mouse arguably operates the world’s greatest consumer products licensing division, it’s relatively modest financially. Only 10% of Disney’s consolidated profits come from the division. This is because Disney doesn’t actually collect most of the profits from its consumer products. Instead, those that design, manufacture, and sell these products do.

Disney could increase its role in consumer products manufacturing and distribution, thereby capturing more of the profits. But what really matters is that if a little girl wants to, she can easily wear an Elsa dress or sleep in Frozen pajamas or a Cars bed. This is incredibly potent mindshare and love-building. It also requires very little storytelling and is brutally hard for a single company to cover. Some people want modernist Star Wars rugs, while others want to express their love for Mickey Mouse through their love for the New England Patriots.

As such, Disney “hires” a third party to manage production and distribution, and compensates them by handing over most of the profit from the sale of associated apparel and merchandise. Disney then monetizes this love in other (more lucrative) areas. The $10 licensing revenue from a light saber is insignificant in comparison to the value of a little boy spending dozens of hours imagining they’re a Jedi Knight.

There Are Costs to Getting Love Wrong (Even if You Don’t See Them Right Away)

In theory, every story should build love. However, it isn’t actually a “required” process — at least in the short term. And again, Disney is a lesson.

The Walt Disney Company’s direct-to-video strategy of the 1990s-era was enormously successful from a monetization (#3) basis. And of course, Aladdin 2, Aladdin 3, Lion King 2, Lion King 1 ½, Bambi II, 101 Dalmatians II: Patch’s London Adventure, The Little Mermaid II: Return to the Sea, et al, were stories (#2). At the same time, they were arguably love withdrawals not deposits (#2). We can tell this in the fact that fifteen to twenty-five years later, many hold affections for Aladdin, Lion King, Bambi and 101 Dalmatians, but few even recall let alone love the stories of their sequels.

Disney’s direct-to-video strategy did more than ignore audience love — it also ended the “Disney Renaissance” and eventually gutted Disney Animation Studios. By the 2000s, the group’s theatrical sales and critical reviews had plummeted (a few films bombed outright). What’s more, fifteen years of lowered standards had sucked out DAS’ creative energy, led many of its top animators and writers to leave, and resulted in Disney missing the rise of computer animation (even though it had pioneered many of the most important advances in 20th century animation). Upstarts such as Pixar and DreamWorks Animation were routinely breaking Disney’s long-running records. Six months after he became CEO, Bob Iger bought Pixar and handed DAS over to Pixar’s leadership. Pixar would fix storytelling, which would lead to love, which would return DAS to monetization.

(In many ways, the Hollywood’s enthusiasm for IP-based money-pump mobile games represents the same strategy — all about #3, with almost none of #1 and a general indifference to #2.)

We can also contrast the MCU, which has excelled with #1, #2, and #3, with franchises that tried for all three but only managed the bookends. In 2016, for example, DC spoke about the irrelevance of critical reviews and exit polling after Batman v. Superman (27% Rotten Tomatoes, B CinemaScore) and Suicide Squad (a barely known franchise in the DC universe that also earned a 27% and B) opened to massive $166MM and $134MM grosses. Two years later, DC’s signature film, Justice League (40%, B+), cratered with a $93MM opening despite starring the three most popular DC characters (Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman).

Marvel’s subsequent Avengers film grossed more in its opening weekend than Justice League did in its lifetime. As did Black Panther, who was largely unknown before his film debut. It’s notable that across 23 films, the MCU has had only one B-level CinemaScore. The DCEU collected two by its third film, even though the average box office haul for these films was higher thanks to the comparative strength of their characters. If you build love, monetization follows. If you underperform, monetization is harmed.

Notably, Disney’s Star Wars franchise also declined as fans bristled at Disney’s creative decisions and mismanagement. Episode VIII grossed less than Episode VII, and Episode IX tumbled even further (grossing half of VII). The second spinoff, Solo, grossed 37% of the first. No one can escape the cost of harming love.

It’s also interesting to think about the Wizarding World franchise (also known as “Harry Potter”), which probably has more untapped potential than any other Western IP (save, perhaps, for Pokémon). This underperformance stems, in part, from the poorly received Fantastic Beasts feature films, as well as J.K. Rowling-related controversies. However, the franchise has mostly been without significant “love building” or ancillary monetization for close to a decade. Since the final entry in the Harry Potter film series in 2011, only two films have released and no major games have been produced. What’s more, the last major Wizarding World book published in 2007 – nearly a decade and a half ago. There has been a stage play, as well as themed lands at three Universal Studios Parks, but these hit only a tiny fraction of total Wizarding World fans. J.K. Rowlings’ Pottermore, a sort of digital publisher-ecommerce-portal-fansite, failed to take off and was largely shut down in 2019. And the film rights have been bouncing and fragmented between NBCUniversal and WarnerMedia since 2016 (and will continue to be through 2025). There are still tens of millions (if not more) die-hard Harry Potter fans globally, but they’re underserved and underdeveloped at a time where competing IPs blanket their fans with ever-more content. Notably, a TV series is now in development at HBO Max.

Love is the Biggest Unlock

It should be clear at this point that I think the most important thing in entertainment is the ability to build love. Anyone can tell a story. Fewer, but still many, can tell a story well. And when stories are told, they typically generate revenue. However, profits, and especially great profits, come from love.

The MCU is so successful not just because its story is better told than peers, but because they better convert to love. This love is easily seen through a ticket sale to or costume purchase of Captain America. However, it’s most valuable when transferred to those who appear alongside Captain America, such as Falcon or Wanda Maximoff. Similarly, love is the great cure-all. It doesn’t matter that Batman & Robin was terrible, or whether the Star Wars Sequel trilogy betrayed you in one entry or another, odds are that you root for a great adaptation of these stories. And thus, while a creative miss might harm a given entry’s P&L, these franchises can quickly rebound through execution (as The Mandalorian has proven).

This is also why we see non-linear returns to the most loved stories versus just “popular” ones (e.g. Star Wars versus The Terminator or Power Rangers). The evolution of Disney’s IP strategy under Bob Iger is similarly instructive. The first half of Iger’s tenure focused not just on tentpoles like Toy Story, Cars and Marvel, but also producing new blockbuster franchises or renewing IP that had been dormant for decades or longer. This included Tron Legacy, Tomorrowland, John Carter, The Lone Ranger, Oz the Great and Powerful. These titles were infamous box office bombs at their worst, and barely profitable at best. This, in turn, led Disney to refocus on expanding and developing franchises that already had a substantial level of love, rather than just awareness (note, too, that after de-canonizing the Star Wars Expanded Universe, Disney is now recanonizing much of it). If you believe that the media industry has, until recently, deeply undervalued IP, then the valuations for beloved IP represented utter market failure.

It’s also here where Disney+ is so important. Disney didn’t need a direct-to-consumer SVOD service to successfully tell stories and build love for them; it has always been disintermediated and thrived all the same. Disney also didn’t need a direct-to-consumer SVOD to collect billions in SVOD profits. Under the “arms dealer” model, it could have just kept making its film and TV shows and collected $6-10B in SVOD “profits” per year just from licensing to Amazon, Netflix, Apple, and HBO. No risk, no investment, no payback period.

Disney+ offers important comparatives advantages to this “easy money”. By bringing all of its franchises and titles together into a single platform, Disney can better tell its stories and build love. Imagine how much harder it would be to build out the Star Wars and Marvel Cinematic Universe if their interconnected series and films were split across multiple streaming services, each with their own release schedule. And even if “everything Star Wars” was sold to Amazon, Prime Video isn’t made for “Star Wars”, nor Disney. In addition, Disney+ is the one place where Disney knows each of its customers, which specific titles and heroes they like most, and helps the company to understand what else they buy across its ecosystem (totes, vacations, toys). In time, Disney+ will come to offer all of these other products, from comics to resort passes, too. All of this helps Disney improve love monetization.

Love Is Always Changing

This can seem like an essay focused on Disney, not storytelling, nor Theodore Levitt. But if you accept that an entertainment company is about love building, that means every entertainment company must be in a process of constant change — from where it tells stories, to where you build love, and how it monetizes.

There was a time in which oral culture reigned supreme, which was eventually supplanted by the stage play, which dominated the middle of the second millennium. Later on, the most popular stories in the world were text-based, from Lord of the Rings to the Chronicles of Narnia, then in radio through Gunsmoke and The Lone Ranger, then film, such as Star Wars, Titanic and The Matrix. Eventually, TV became the best medium for love building and incubation. It’s unlikely that Game of Thrones could have found an economical audience through theatrical films, so too The Walking Dead (collectively, these series were the most popular scripted shows in the United States for close to a decade). Similarly, TV is now being used to rehabilitate hydroplaned franchises like Star Wars, or enrich lesser known characters, such the stars of WandaVision or Ms. Marvel. Many of these video-centric franchises originated in other mediums, however, their popularity influence peaked through film/TV.

Music is another fascinating example. The entire industry used to tell its stories through the album format, build love primarily through the album, and monetize through it too. But over time, the concert experience and art form improved substantially while the barriers to music creation fell precipitously. As a result, live music became key to any album’s “story”, one of the most important channels for love building, and the most remunerative one, too. For many artists, music isn’t even the core of their monetization strategy, just the place in which their brand’s story is told and where love is instilled. Kanye, Rihanna, Jay-Z, et al, have made far more money outside music than in it. Much like celebrity athletes such as Ronaldo or David Beckham. Investor Chris Dixon recently argued that music-related NFTs are so powerful because they allow musical artists to, for the first time in the digital era, sell a new thing rather than just the old thing (a song) a new way.

Then there’s the enormity of Travis’ Scott’s Fortnite concert. Nearly 30 million people spent nine minutes fully immersed in his music. This included die-hard and casual fans, non-fans and people who didn’t even know he existed. There is no other experience on earth — including the Super Bowl half-time show — that can deliver this degree of reach and attention, COVID-19 or not. The track Scott premiered during the concert (The Scotts, a collaboration with Kid Cudi) debuted at #1 on Billboard a week later. This was Cudi’s first Billboard #1 and the biggest debut of 2020. In addition, several of the tracks Scott performed from his two-year-old Astroworld album returned to the Billboard charts. And many millions of dollars of virtual Scott goods were sold.

The constant changes in 1-2-3 speaks to how the entertainment industry is changing beyond “D2C SVOD”. The two clearest trends are video gaming/interactivity and multi-media/trans-media/cross-media storytelling. Taken together, this will fundamentally alter competitive dynamics, which stories we love, and how much.

Love Changing #1 – Gaming as the New Frontier for Love

Over the past twenty years, many new franchises have been born or elevated, from Twilight to Game of Thrones. And many of the biggest franchises, such as Star Wars and Marvel, have grown stronger. But in aggregate, the medium that has generated the most new love is video games.

This explains why, after spending two decades trying to create whole cloth new IP or modernize old European IP via film/TV, Hollywood is now rushing to adapt titles like Halo, Super Mario, Diablo, Sonic, The Legend of Zelda, The Last of Us, Bioshock, Metal Gear Solid, Fallout, Pokémon, and more. These titles have now collected multiple generations of fans (love building) and benefited from several reboots and technical advancements that have substantially grown its storytelling sophistication.

Related Essay: Why Gaming IP Is Finally Taking Off in Film/TV

We can tell how powerful gaming’s love-building (#2) advantages (i.e. immersion, agency, interactivity) are because most would argue the storytelling (#1) remains much weaker on average. Consider the fact that we laugh more in a movie theatre than when watching a movie at home — and more at home with a partner beside us than alone. Gaming is increasingly a medium that’s optimized around the very elements that explain this dynamic — the potency of social, collective storytelling experiences.

And crucially, game publishers aren’t licensing their IP for adaptation to film/TV to monetize (#3), but to instead to grow love for their content (#2) through new types of stories (#1). Microsoft, which has a $1.9 trillion market cap, doesn’t need a few million from $30B ViacomCBS for the rights to a Halo TV series (due on Paramount+ this year), nor is this fee going to exceed annual profits from the Halo game. There is no better evidence that power dynamics have changed from linear video to video gaming; game publishers are effectively paying Hollywood (via the majority of profits from adaptation) for building love and fans for their franchises. These are the stories of tomorrow.

Just as gaming seeks Hollywood to adapt their stories in order to build love, Hollywood seeks out gaming to adapt theirs. But in this latter case, Hollywood faces existential threats.

Five years ago, EA had only one Star Wars title. Now it has a multiplayer action title (Star Wars: Battlefront 2), a single player adventure franchise (Star Wars Jedi: Fallen Order), a multiplayer space combat title (Squadrons), a free-to-play mobile collectables RPG game (Star Wars: Galaxy of Heroes), one MMO (Star Wars: The Old Republic), and is reportedly working on a sequel to its best-selling MMO series (The Knights of the Old Republic) as well as remakes of the first two titles.

More broadly, several of the best stories told in the Star Wars universe since 1983’s The Return of the Jedi have been told in games, not film or TV (not all were made by EA, though several were). In 2020, fans spent more time with The Avengers in Fortnite than they did in 2019 with Avengers: Endgame. These experiences offer far more immersion, far more easily, and to far more people than Disney’s parks, consumer products, or SVOD can. It also made many characters, such as Doctor Doom and She-Hulk, familiar to and popular with audiences for the first time in decades.

In many respects, this is good for Disney: more stories, more love, more monetization. At the same time, EA has been responsible for an ever-growing share of Star Wars’ stories (#1), love building (#2) and profits (#3). EA owns the customer relationship and data, too. And it is, of course, building its own D2C consumer media platform and storytelling ecosystem.

Lucasfilm Games’ recent decision to diversify its Star Wars licenses to other publishers, such as Ubisoft, moderates the extent to which Disney’s Star Wars franchise will build up any one gaming ecosystem. But it does not build up Disney’s ability to meet consumers in the category telling the most inventive stories, generating the most new love, and that is rapidly becoming the best-monetizing entertainment category globally.

And unlike in streaming video, there’s no quick way to catch up — Disney can’t just buy a backend game service provider, reclaim the back catalogue of Disney-based games, and become a leader. Producing games, and live operating them, is a fundamentally different skillset than figuring out how to stream linear content over the Internet. And Disney does not own or ever “get back” the library of Star Wars or Marvel games that have been made over years — nor is there demand to replay them similar to that of the Disney Vault of films.

In contrast to licensing Captain America to Mattel for a plastic shield, video gaming is more narrative, more important, and differentiated. This is not an area where a media company can just pick to enhance” love”. It must own it, the story, and the fullest dollar. You also can’t learn how to tell a great gaming story or make a great videogame through licensing and without any real access to player data.

Furthermore, publishers typically do not assign their top creatives or concepts to licensed titles. Which makes sense! Publishers maximize their returns by focusing on properties they own royalty free and in perpetuity. This model can also suffer from the principal-agent problem. Licensees, after all, are less focused on the long-term strength of the underlying IP than instead maximizing the value they collect while its theirs to use. This led Disney to publicly condemn EA’s monetization model for Star Wars: Battlefront 2 and force change. And even when the principal-agent problem isn’t at work, licensees aren’t in the business of supporting their licensor’s other objectives (e.g. selling movie tickets or merchandise).

As this essay has likely made clear, Bob Iger was an astonishingly successful leader. One who led transformation in content, business model, and scale. But he had a large failure. And it wasn’t failing at video games, it was telling Disney that they would continue to fail and should stop trying to succeed in the category directly. Consider the following from 2019, which was delivered via a quarterly analyst call.

We’re obviously mindful of the size of the business. But over the years, as you know, we’ve tried our hand at self-publishing. We’ve bought companies. We’ve sold companies. We’ve bought developers. We’ve closed developers.

We’ve found over the years that we haven’t been particularly good at the self-publishing side, but we’ve been great at the licensing side, which obviously doesn’t require that much allocation of capital. Since we’re allocating capital in other directions, even though we have the ability to allocate the capital, we’ve just decided that the best place for us to be in that space is licensing and not publishing.

We’ve had good relationships with some of those we’re licensing to, notably EA and the relationship on the “Star Wars” properties. We’re going to continue to stay on that side of the business and put our capital elsewhere. We’re good at making movies and television shows and theme park attractions and cruise ships and the like. We’ve just never managed to demonstrate much skill on the publishing side of games.

There are many reasons to believe Disney can be good at games, but first, the company has to decide that it must be. Just as it did with streaming video and direct-to-consumer. If gaming had existed when Walt Disney drew his famous flywheel diagram, it’s impossible to believe he would have placed the category on periphery, let alone outsourced it to a rotating roster of third parties who oversaw both creative and distribution.

Love Changing #2 – Transmedia as the Final Frontier

When Netflix’s The Witcher TV series started streaming, The Witcher 3 video game saw its player count grow 3-4x, and the thirty-year-old book series returned to the New York Times Best-Seller list for the second time ever and received a 500,000-copy reprint for the US alone. George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series had sold roughly 15MM copies over its first fifteen years. In the decade following the premiere of the Game of Thrones TV series, some 90MM more copies were shipped.

These are not examples of trans-media storytelling. They do, however, speak to the growing desire to keep experiencing a story world, even to the point of duplication. And with Star Wars, Marvel, and DC uniting their film, TV and comics universes (while Fortnite expands into comics), it’s clear the next “phase” of storytelling will extend into gaming. The rise of virtual production and real-time rendering via game engines will supercharge this trend. Suddenly, a physical studio backlot and digital backlot will merge to become a truly virtual, with assets shares across all mediums.

There aren’t many companies that can pull this off. It requires unique IP, diverse capabilities, plus unprecedented coordination across every business unit and creative. No one has this in place today, and the hands are fairly distinct.

The major tech companies, such as Amazon, Google, and Apple, are bad at IP, games, or video (if not all three). Disney excels at IP universes and is building up expertise in film-to-TV transmedia, but it has no interactive assets. At the same time, this could change quickly via acquisition — and the applicability of theme park expertise should not be overlooked. Warner Bros. is unique in that it excels in gaming, film, and TV — and has its own direct-to-consumer platform. However, it is comparatively earlier in cinematic universe building and social, world-based gaming. Done right, this “transmedia universe” could be the path to surpassing Marvel — just as Marvel’s Cinematic Universe model was used to surpass the rest of the industry.

Sony is another leading candidate. Over the past twenty years, no one has created more globally resonant (and largely narrative) IP, from God of War to The Last of Us, Horizon Zero Dawn, Uncharted, Death Stranding, and the PlayStation Spider-Man series. More impressive still, Sony has done this under a largely decentralized studio model. These titles (and other gaming-native IP, such as Metal Gear Solid), are now being adapted to film/TV by Sony Productions. Sony also boasts its own virtual production arm, while Sony Immersive Studios recently partnered with Sony Music to produce a live, virtually produced VR concert with Madison Beer (Example, Example). And then there’s Sony’s market-leading PlayStation console platform and close partnership with Epic Games. But, corporate integration has always been Sony’s biggest obstacle (hence missing the MP3, smartphone, CTV, and SVOD market opportunities despite the aforementioned assets). In addition, Sony is weakest in online multiplayer, UGC, and live operated “worlds”.

Riot Games already operates one of the world’s largest video game franchises (League of Legends) and has long envisioned itself as a modern Disney. Over the past two years alone, the company has launched three LoL spinoffs (an auto-battler, mobile MOBA, and digital collectable card game) — with several more to come. This year will also see the release of Arcane, a League of Legends anime series that was mostly developed in-house at Riot and will be the most expensive animated series in history (by multiples, per reporters). Riot also “operates” a virtual K-pop girl group composed of LoL heroes that has already topped Billboard global streaming charts on two occasions, and the squad’s first music video hit 100MM views on YouTube in a single month (and is approaching 450MM today). Last fall, the company hired its first-ever Chief Marketing Officer.

Nintendo is another fascinating example (as I wrote in detail last year). The company spent the late 1980s and early 1990s looking to extend its IP through third parties. However, this led to a string of creative, commercial, and reputations disappointments, including the lackluster The Super Mario Bros. Super Show!, infamous Super Mario Bros. movie, and the even worse series of Legend of Zelda games made by Philips for its CD-I console. This led the already-conservative Nintendo to drastically reduce all licensing activities for close decades (Nintendo owns less than third of and does not creatively manage The Pokémon Company, which does have a large-scale consumer products and animation business). But by the mid-2010s, Nintendo began to rapidly open back up. The company struck deals with NBCUniversal to co-develop several themed lands for its parks, then for its Illumination Entertainment division (which Minions and Secret Life of Pets) to produce the first Nintendo movie in more than thirty years, Super Mario. The first in a series of digitally-enabled Lego kits also shipped last year, as did an AR mobile game made in partnership with a mid-stage start-ups, Velan Studios.

Nintendo’s evolution speaks to the nearly universal mindset shift in the gaming industry. The potential licensing fee from a TV adaptation, or profit sharing from a theatrical adaptation is tiny compared to the potential of a wholly owned hit game. In addition, a failed adaptation can do enormous harms to love (i.e. players can end up disappointed, if not embarrassed). But today, there is no fan “top of funnel” as wide as a hit film or TV series. Still, Nintendo’s license requirements and strategy is worth emphasis. Specifically, the company mandates that there are to be no story deviations, characters, or attributes that might “limit future game development”. This is an incredible broad constraint that doubtlessly limits the stories that can be told (#1) and the profits collected (#3). But for Nintendo, everything that isn’t a game is intended to build love among current players or to generate new ones. Furthermore, Nintendo is uniquely disinterested in profit maximization. Instead, it is obsessed with telling only the best possible stories.

Related Essay: Nintendo, Disney, and Cultural Determinism

Why Does This Truly Matter?

Entertainment companies today don’t make movies or TV shows. They don’t even mainly “tell stories”. They manage the proprieties of those stories in such a way to create and sustain deep affinity, i.e., build love.

This is a very different rubric than the media industry is used to. It also suggests that many low-margin businesses, products, or titles create more value than an income statement might realize. Think about the correlation between the pajamas you wore growing up and the adaptations you deeply want to succeed, versus those you’re largely indifferent to. It’s doubtlessly true that the comics divisions of Warner Bros.’ DC, and Disney’s Marvel deliver minimal revenues and dilutive margins. But comics remain a low-cost channel for story and love building.

Notably, almost all of the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s forthcoming series are from the last (and largely unknown) decade of comics. It doesn’t matter to maestro Kevin Feige that his films have eclipsed not just the comics by several literal orders of magnitude, nor even all of film history. These comics are where new stories are created, discovered, and refined. The now globally famous character of Miles Morales first appeared in 2011, Ms. Marvel (who has her own MCU TV series this year) comes from 2013. Riri Williams, who will take up Iron Man’s mantle in her own MCU TV series first appeared less than five years ago.

Imagine if Disney had shut down Marvel’s comic book division in 2010. Marvel Studios, its parent Marvel Entertainment, and its parent The Walt Disney Company, would have been essentially unaffected for more than a decade. But then suddenly, Marvel would have begun to run out of new stories and characters (especially those that looked beyond the typical cishet white egoist tropes) — and there would be no way to quickly make up for a lost decade of iteration and market testing.

This trend also means that Hollywood needs to solve its video game problem. The category simply matters too much to audiences. It is also becoming more social, immersive, and narratively rich each day. Consider the evolution of TV/video versus games over the past fifteen years. The MCU films and series of 2021 are more interconnected, complex, and visually impressive than 2008’s Iron Man, but they’re still rather similar. Games, meanwhile, have been entirely reinvented for live services, social multiplayer, and UGC. Now, we’re only a few years from the point in which millions will come home to join a live event with a real-time motion capture hero like Tony Stark (who will likely not be performed by Robert Downey Jr., even though it will look like him) alongside their friends. Not long after, these will be integrated into the weekly release schedule a TV series, thereby enabling the audience to help the heroes as they watch them.

This also connects to Disney’s greatest love advantage: it’s theme parks. For all the success of Disney+, the strongest, most profitable, most defensible part of Disney’s business is its capex-heavy, physical theme parks. As I wrote in “Digital Theme Park Platforms: The Most Important Media Businesses of the Future”, “there is no simple way to quantify how important this business unit is to Disney… The financial role is obvious… [but] There is nothing that can compare to the impact of a child being hugged by her heroes. The ability to enjoy your favorite IP as “you” is unique and lasts a lifetime.” The problem with Disney’s parks, however, is that they can only ever reach a tiny portion of Disney’s fans (and rarely its lower income and foreign fans). And it takes tens of billions of dollars and close to a decade to reach more (which is why most of Disney’s competitors lack parks, despite their importance and profitability).

Digital theme parks, however, “are always ‘open’, ‘everywhere’, ‘full of your friends’, and impervious to COVID-19… They also boast an even larger (i.e. infinite) number of attractions and rides, none of which need be bound by the laws of physics or the need for physical safety, and all of which can be rapidly updated and personalized. These digital parks also allow for much greater self-expression (e.g. avatars, skins).” And soon, every fan will be able to receive a hug from the actual Iron Man.

This isn’t to say an IP holder needs to own a gaming studio, per se. Obviously that’s an advantage in a number of ways, but at minimum, every IP owners needs cohesive and comprehensive strategy for interactivity that goes beyond MGs, GGs, and avatar licensing.

What does all of this mean for the industry overall? Well, one of the key lessons over the past several decades in entertainment is one of “more”. We want more of the stories we love, more often, in more places, and more media, always. We might gripe about how Disney will never let Star Wars end or that endless sequels undermine the significance of any films that came before, but the truth is only we want something to “end” ... until immediately after it does. Give us The Mandalorian, even as we tire of the sequel trilogy, and then second season of The Mandalorian one year later. We hated the prequels but delight at the idea of a spinoff of Ewan McGregor’s Obi-Wan. Two Star Wars games aren’t enough, nor is four. Just look at gaming over the past year and a half. Yes, the pandemic led us to play more games, but mostly we played our favorite games more.

If our biggest stories become bigger, and ultimately, we want endless amount of “more” from our favorite stories, then most of us will hit a sort of “Dunbar’s Number” for franchises. The bigger Marvel (or anyone) gets narratively, in love building, and in monetization, the harder it will be for a Power Rangers reboot or Dark Universe or Transformers Ecosystem to grow. Consider the mocap example. We’re not going to run home to mocap every hero we know of, even if we watch a diverse selection of hero movies. The same applies to AR. It’s a delight to “light up” the world around you with your favorite IP, such as Pokémon or The Avengers, but we can only “main” so many words. This means fewer stories will collect ever-more of the benefit.

There used to be a fight to be one of the winning comic books, video games, or film franchises. This meant there was room for many winners and that the reach of any winner was limited. Soon, it will be a fight for dominance between all franchises and across all mediums. The major stories will expand into all categories, from film to TV to podcasts, and be envisioned as interactive experiences. And as long as they continue to offer more “more”, there’s little reason for a fan to look (and invest) elsewhere.

This doesn’t mean smaller stories won’t exist, be consumed, or be popular — but they’re likely to be snacks and sides. Just like non-franchise films are at the box office today. It’s also likely that we’ll continue to see new franchises emerge and old ones fade. However, the IP business is fueled by love and monetization feedback loops. Those who do it best and most will win. And the threshold is going up.

Matthew Ball (@ballmatthew)