The Tremendous Yet Troubled State of Gaming in 2024

Preface (Added 28 February): The purpose of this essay is to explain the growing crisis faced by the video gaming industry. And crisis is a fair characterization. In 2022, the industry had a then-record of 8,500 layoffs. 2023 beat that record by nearly 25%. And during the first two months of 2024, there have already been some 8,000 job losses. Alongside (and partly behind) these layoffs are scores of games that underperformed or flopped altogether — and many more in-development titles that have been canceled outright. Few expect these layoffs or game shutdowns to stop, though they may slow. At the same time, the video gaming industry continues to achieve new cultural highs, while many of its most popular titles, profitable publishers, and powerful ecosystem continue to grow. This leads to the second purpose of this essay: explaining the apparent contradiction between the industry’s successes and its struggles.

Crises have many causes (and so this essay is also quite long, too): The end of the COVID-19 pandemic and low-interest rates are partly responsible, but so too are changing business models, evolving user behaviors and preferences, labour economics and microeconomics, disappointing forecasts (and only-recently abandoned rationales for the related shortfalls), competitive and budgetary escalation, console saturation, and an end to the growth-drivers of the last five and ten years. It is the convergence of these many trends that is behind the current state of gaming. These problems will eventually pass, and there are many reasons for hope, but it will likely take time.

- - -

To players and outside observers, 2023 looks like one of the 70-year-old gaming industry’s greatest-ever years. Chief among its achievements was its slate of new software releases. PC and console players received Alan Wake 2, Armored Core VI, Baldur’s Gate 3, Diablo IV, Final Fantasy XVI, The Finals, Hi-Fi Rush, Hogwarts Legacy, Marvel’s Spider-Man 2, Starfield, Star Wars Jedi: Survivor, Super Mario Bros. Wonder, and The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom, alongside the Cyberpunk 2077 2.0 re-release (plus Phantom Liberty DLC), Fortnite OG, Metroid Prime Remastered, and the Resident Evil 4 remake, with Roblox finally launching on PlayStation. On mobile, Monopoly Go! and Honkai: Star Rail debuted, while the Indian ban on PUBG Mobile (previously the most popular AAA game in history) was lifted. It’s difficult to argue any other year has seen a greater slate (yes, even compared to 1998 and 2007). AW2 was my personal favorite.

Hardware had a terrific year too. After two and a half years of supply constraints, it was finally possible for anyone who wanted to purchase a Generation 9 console (PlayStation 5 and Xbox Series S|X) or a new top-of-the-line graphics card to do so. In October, Meta’s Quest 3 finally released, offering substantial improvements to 2020’s Quest 2, which sold roughly 20 million units, or 20 times more than 2019’s Quest 1. PC gaming leader Valve also released an updated Steam Deck (offering OLED, a 0.4-inch-larger screen, 50% faster frame rate, etc.), and console leader PlayStation launched its VR 2 (the first model launched in 2016) and the PlayStation Portal (which enabled PlayStation 5 owners to play their console via a handheld device, although only inside the home).

The largest platforms grew as well. Roblox, the most popular gaming ecosystem globally, grew its daily active users from 59 million in Q3 2022 to about 70 million in Q3 2023, with monthly active users growing from 275 million to 350 million and monthly hours from roughly 4.6 billion to 5.6 billion. In its seventh year, Fortnite, which had generated more revenue in a single year than any game in history during both 2018 and 2019, achieved new highs in its daily and monthly active user figures after launching its “UEFN” (Unreal Editor for Fortnite) overhaul to Fortnite Creative as well as LEGO Fortnite, Rocket Racing (a spinoff of Rocket League), and Fortnite Festival (a reimagination of Rock Band).

The strength of gaming was also demonstrated well beyond its own market. Nvidia, a thirty-year-old company that built its business around gaming (founder/CEO Jensen Huang has said this focus was “one of the best strategic decisions [the company] ever made”), also became one of the world’s largest, most powerful, and important companies in 2023 through the rise of AI. Microsoft also completed the largest tech acquisition in history, buying not an enterprise software giant, AI pioneer, or smartphone manufacturer but Activision Blizzard, owners of Call of Duty, Warcraft, and Candy Crush. And at $70 billion, this purchase cost fully nine times what Amazon spent on a TV/film-maker such as MGM, was twice the value of streaming music leader Spotify, and had a greater enterprise value than Hollywood giants such as Warner Bros. Discovery, Paramount Global, NBCUniversal, or Lionsgate (indeed, even some of those players combined). Reports also emerged that, after three years in market, Netflix was looking to evolve its gaming offering from a bundled and purely-free-to-play part of its video subscription into one supported by ads and microtransactions. Such a shift could mean Netflix’s business wasn’t working in its current state, but as the “streaming bubble” collapsed in 2022 and 2023, it was hard not to look at the major gaming publishers and see exactly what many Hollywood giants had once sought in streaming video but had since determined to be illusory — tens if not hundreds of millions of D2C users and a profitable, consistently growing business behind it.

IP is another area where gaming soared to new and considerable highs in 2023. The Super Mario Bros. Movie grossed $1.4 billion worldwide, ranking second for all theatrical releases in 2023 and third among all animated films in history; it more than tripled the box office of 2019’s Detective Pikachu, which had held the record for a video game adaptation. Five Nights at Freddy’s was a surprise hit, too, grossing $300MM worldwide on a $20MM production budget at Universal—outstanding in its own right but also more than twice the haul of Universal’s Exorcist: Believer, which came out two weeks earlier and fell short of $140MM worldwide (Universal reportedly paid $400MM to acquire the rights to the franchise). HBO’s The Last of Us, which adapted the hit PlayStation game of the same name, was the first video game adaptation nominated in major Emmy categories and was the second most nominated series of its year, collecting nods for Outstanding Drama Series, Outstanding Lead Actor, Outstanding Lead Actress, Outstanding Director, four of six nominations for Outstanding Guest Actor (with one winning), three of six nominations for Outstanding Guest Actress (with one winning), and twelve other creative nominations (six wins). According to HBO, the series was its most watched since 2011’s Game of Thrones, meaning that it also beat 2022’s Thrones spinoff House of the Dragon. Peacock’s Twisted Metal adaptation became one of its five biggest original series launches as well as its most binged comedy.

Video games did more than thrive in film/TV during 2023; they are helping to revive and expand non-gaming IP. Each of the last three films set in the Harry Potter universe set a new record low at the box office, with the 2022 entry grossing only $407MM worldwide, after which Warner Bros. effectively cancelled the last two entries in the five-part Fantastic Beasts series. Many analysts attributed the poor performance to the absence of the Boy Who Lived, among other issues, even though the Fantastic Beasts series was a direct prequel to the Harry Potter films and starred Dumbledore himself. Yet 2023’s best-selling game by unit sales is set to be Hogwarts Legacy, which grossed $850MM in its first two weeks alone and will likely cross $1.2B. Not only is there no Harry Potter in Hogwarts Legacy but the title is also considered non-canonical and thus has even looser ties to the master franchise than Fantastic Beasts did.

Another big 2023 game, Star Wars Jedi: Survivor, is a canonized tale produced by EA that, like its 2019 predecessor, has massively expanded the number of Jedi to survive “Order 66” and produced many fan favorites, such as lead Cal Kestis, who seems destined to appear in live action (and happens to be played by Hollywood actor Cameron Monaghan). Despite strong reviews, the 2023 film Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves sold only 3.5MM tickets globally, producing roughly $208MM in revenue, half of which was retained by theater operators. Though the film will benefit from ancillary revenue streams (SVOD licenses, home video sales, etc.), it’s unlikely to see much profit on its $150MM production budget and $50MM for marketing. A sequel seems unlikely. In contrast, the 2023 game Baldur’s Gate 3, which is based on the same D&D tabletop IP, has sold 6–7.5MM copies and at several times the price, generating over $500MM in revenue and winning Game of the Year at the Video Game Awards.

Of course, one can find high-level disappointments even in a year as great as 2023. For a time, the Nintendo Switch 2, Apple Vision Pro, and even GTA VI were expected to launch by the holiday quarter. Not all games met the lofty expectations of its target players. But what a year. In theory.

Princess In Another Castle

For those who worked in gaming, last year was brutal. A record 10,500 game developers, artists, testers, and other gaming employees were laid off in 2023, topping the prior record holder, 2022, which saw 8,500 in job losses. Unfortunately, 2024 has seen 3,950 in cuts in only 22 days 5,850 in cuts after only 25 days 6,200 cuts after only one month 8,500 in cuts after only two months.

These layoffs went deep, too. Niantic cut roughly one in four employees (and cancelled several titles), Epic Games cut 16% of its staff (and divested several percentage points more), Unity laid off 15% last year (and then another 25% in January 2024), Riot dropped 11%, CD Projekt Red shed 10%, while Microsoft gaming lost 8.6%, Sony PlayStation 8%, Bungie 8%, with EA at 6% in 2023 and another 5% in 2024, while Ubisoft’s precise numbers are not known. Amazon laid off more than a thousand employees across its various gaming divisions, including Twitch; As Embracer continues its widely-predicted implosion, trying to summarize which groups and people have and haven’t been laid off is futile. These figures are limited, too, as they don’t count venture-backed startups, nor the many gaming journalists laid off at The Washington Post, Kotaku, Inverse, Waypoint, etc., outlets that by rights should benefit from gaming’s ascendency. There are other drawbacks to just focusing on layoffs. In Q4 2023, ByteDance announced it would sell and shut down the entirety of its gaming division — even though it had become one of the most powerful, popular, and revenue generating companies in the world (crossing $100B in annual revenue in mid-2023). The company essentially shut down its Pico VR/MR division, too, even as Apple geared up.

There are several reasons behind the many layoffs detailed above, but the first may be the most important. It’s also the most overlooked and most counter-narrative: video game revenues are falling. And the explanations (excuses) touted throughout 2021 and 2022 have since been invalidated and in the process, put darker clouds over forecasts that were already being revised downwards.

In nominal terms, U.S. consumer spend on video games (including software, hardware, and accessories across all platforms, but excluding Web3/NFTs) was $57.2 billion in 2023, up only 1.1% over 2022, which had fallen 5% versus 2021. Compared to 2021, spending in 2023 is therefore still down 4.1%. Compared to 2020, revenues are up only 2.0%, with an anemic 0.7% compound annual growth rate (CAGR). 2019 is the most favorable comparison, as 2023 is up 27% since (6.2% compounded), but this reference frame is misleading, as 91% of the growth happened in 2020.

These are not great numbers. And worse still, these numbers are nominal in a time that has seen 40-year highs in inflation, with average U.S. CPI up 19% since 2019. In real terms, U.S. gaming revenues in 2023 are 2.1% under 2022, 14.3% under 2021, 13.6% under 2020, and up only 6.9% from 2019 (1.7% CAGR). In contrast, real GDP growth in the United States has averaged 2.0% annually since 2019 and 3.1% since 2020, meaning that the gaming industry has fallen well short of the average sector for three years. This shortfall occurred despite the first industry-wide price hike for premium games in decades, with many publishers announcing that new releases for Generation 9 consoles (which launched November 2020) would be $70, not $60, a jump of nearly 17%.

Weak revenue growth is not sufficient to explain the rash of layoffs—companies can, by definition, survive on the same revenue as before and probably on a bit less, too. Yet costs for game makers have grown considerably during this period, too.

Most Western publishers will say that their per head costs are up between 15%–20% since the pandemic. These record-setting increases have several causes. Most obvious is inflation, which has necessitated cost-of-living adjustments. Yet inflation has far outstripped revenue growth and COLAs both, which means that many publisher gross margins are falling and real incomes for their teams have fallen despite material increases. Furthermore, inflation remains well-above market rates. In theory, record job losses should ease talent costs, but there are several non-inflationary reasons for surging costs. For example, the number of experienced game developers, artists, testers, etc., has fallen short of the growth in the number of game developers needed to make many games (more on this later). Over the past several years, there has also been a growing focus on improving employee benefits and reducing “crunch” (the industry lingo for long hours), both of which produce increases in costs per hour (however necessary). Some studios report that the shift to remote or hybrid work has harmed productivity (though others disagree and remarkable games have been produced under this model).

Many developers, especially those who build or use AI in games, are also being poached by big tech companies that offer far higher compensation. And between 2019-2022, there was an abundance of venture capital funding available to video game start-ups, which allowed these companies to offer developers high salaries and large equity incentives that blue chip gaming companies struggled to match. In response to increasing regulatory scrutiny at home and growing, Chinese giants such as Tencent and NetEase also began standing up their own North America and European studios, and similar to highly capitalized venture-backed start-ups, offered high signing bonuses, salaries, and equity (or really, profit sharing). The net result is that even a 10-15% reduction in employee counts, or a reduction to January 2021’s employee count, still leaves companies with much higher cost structures and probably against lower revenues, too.

No game-makers budgeted for 40-year highs in inflation. Nor did they budget for revenue stagnation. Most internal and external market forecasts suggested uninterrupted secular growth and at a rate faster than real GDP (one top consultancy has a 2022 forecast for 2025 that will be 25% too high, one top investment bank has a forecast from 2021 that overshoots 2025 by 30%, there are others but it’s gratuitous to call them all out). After all, few industries ride Moore’s Law as hard as video gaming! But not only has gaming underperformed most sectors, it’s one of few media categories to shrink. The “streaming wars” are causing pain across film and TV, yet consumer spending continues to grow year-over-year. Revenue for audio, inclusive of the secularly declining terrestrial radio segment, is up 20% from 2020. Book publishing, too, is up 14%. The only decliner is newspapers and magazines, which have been in free fall for more than a decade, and no one is expecting a sudden return to growth (the decline did slow, however). This brings us to one of the fundamental surprises of 2023, that the stagnation (if not outright reversal) of revenues persisted into that very year.

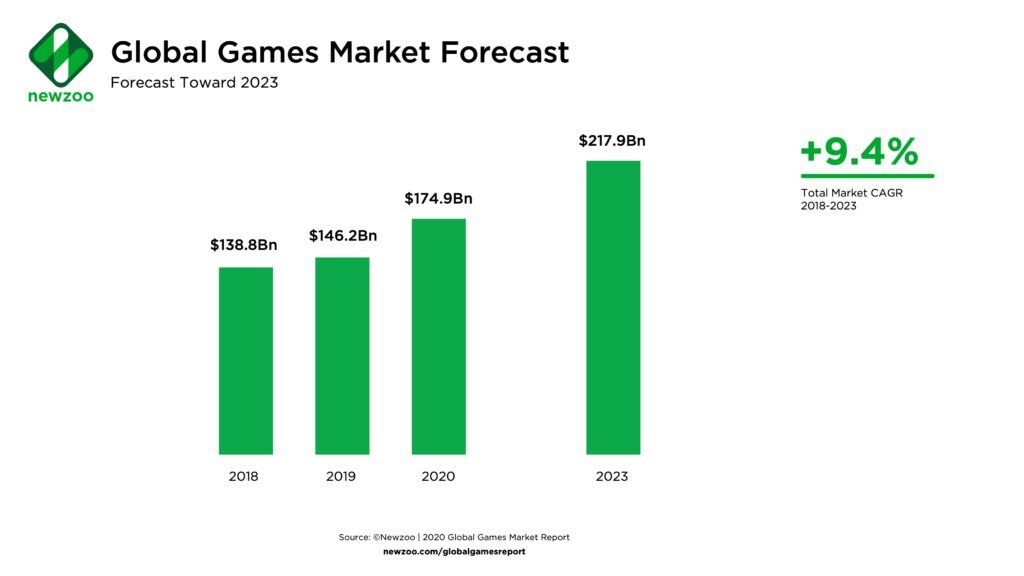

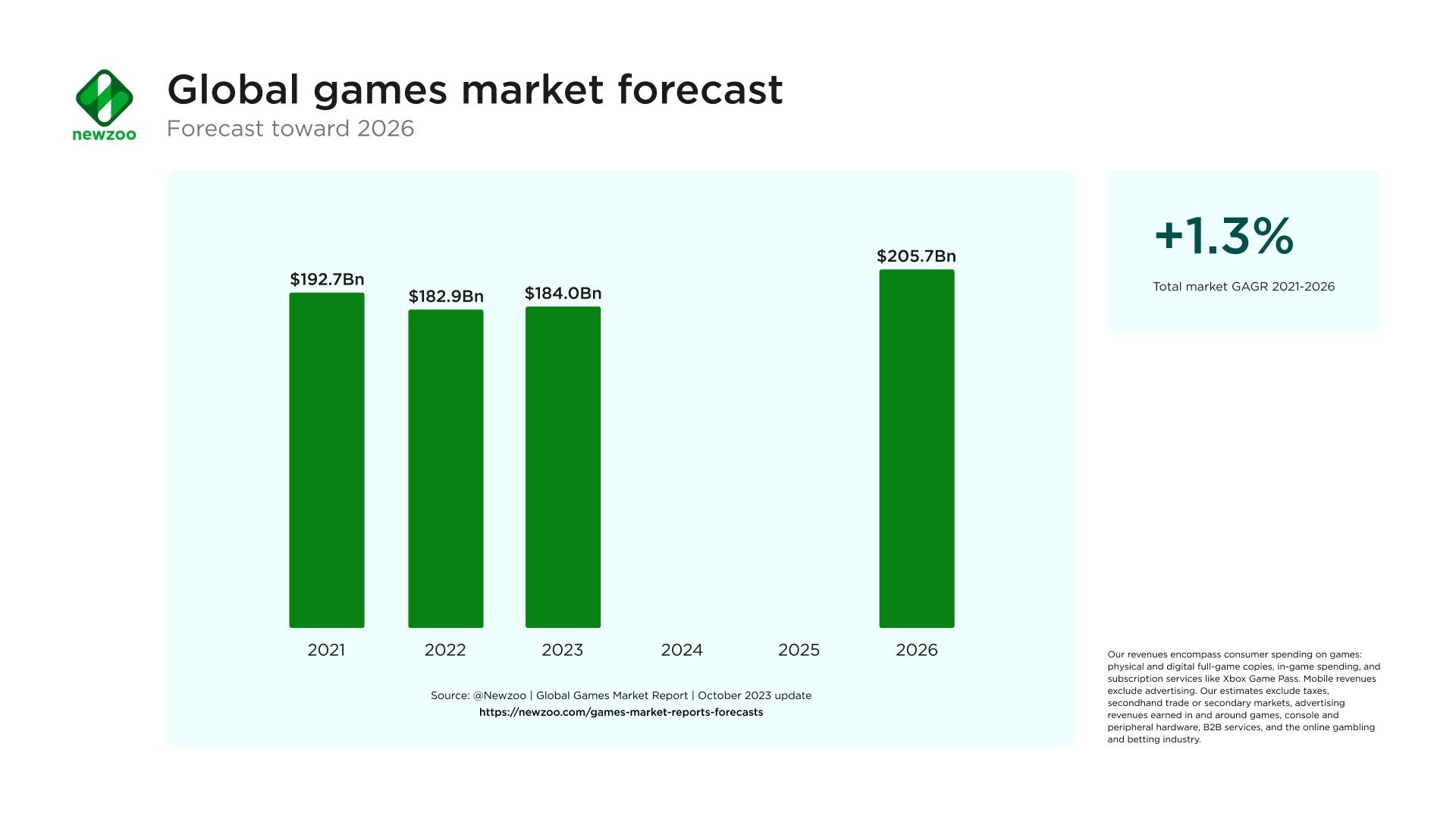

Newzoo’s 2020 Forecast for 2023 | Newzoo’s 2023 Actuals and Forecast for 2026

When gaming contracted in 2021 and 2022, the most common explanation was the relative lack of marquee releases. Many titles once planned for 2021 and 2022 had been delayed, largely due to the COVID pandemic; some argued that the quality of the titles that did find release had suffered, for much the same reasons. There’s no counterfactual for these years, but this logic suggests that 2023’s outstanding release slate should have led to significant growth in software revenues. Instead, 2023 finished with software (i.e., content) sales of $48.0 billion, up only 1% in nominal and down 2.1% in real terms from 2022, and +5.6% and –15.7% from 2021.

Another argument ran that the scarce supply of Generation 9 consoles and top-of-the-line graphics cards was holding back revenues. The theory had three prongs. First, the inability to find a new Xbox, PlayStation, or Nvidia GeForce RTX meant that consumers could not spend on these devices, which typically comprised 10–12% of annual video game spending. The shortage also limited accessories revenues, another 4–5% of total spending, as some secondary gaming devices, such as a monitor or headset, need to be replaced for the player to take advantage of their new console or GPU.

Software sales were hit by hardware scarcity, too. Some of the titles released over the past few years, such as Horizon Forbidden West — Burning Shores, were only available on Generation 9 consoles. And those that supported both Gen 8 and Gen 9 were, as discussed, roughly 17% more expensive if bought for Generation 9 devices. It is also, presumably, easier to sell new games when they’re played on cutting-edge hardware, rather than decade-old ones, and so the Gen 9 console and top-of-the-line GPU shortages were a constraint here, too.

Consoles are now widely available, yet spending is up only 0.2% year-over-year, and while sales are up 8.7% versus 2021 (when devices were at their most scarce), it has not led to a software boom. Yes, hardware can in theory cannibalize software spend, but the relative price point ($300–$500) should more than compensate.

A more pertinent constraint was Apple’s April 2021 deprecation of IDFA, which allowed advertisers to identify iOS users based on a unique device ID, and revised app tracking transparency policies, which enabled users to opt out of app-based tracking solutions. Altogether, IDFA and ATT (plus Google’s similar GAID and PSOD) harmed the mobile gaming economy (roughly 40% of U.S. gaming spend) in three interconnected ways. First, it reduced the ability of mobile ad networks to deliver personalized ads to these users, which diminished ad efficacy and thus also the ad revenue generated from play (roughly a third of all U.S. mobile gaming revenue is ad-based, with the remaining two thirds coming from user purchases). As one of the largest buyers of mobile game ads is the publishers of other mobile games, reductions in mobile app ad efficacy brought second- and third-order effects. For example, it increased the cost of user acquisition, which meant that some would-be players could not be economically acquired and thus weren’t, leading to fewer games being installed, which in turn limited total playtime, which limits spending and further harms ad revenue and game discovery, and so on.

Unsurprisingly, Sensor Tower reports that mobile gaming downloads peaked the quarter before Apple introduced its IDFA/ATT policy changes, with 664MM unique game installations. A year later, installs were down 4% (or –26MM), down 18% two years later, and are now down 26% despite (the sustained decline reflects the many compounding IDFA/ATT interactions). Android, which began its policy changes later and was slightly more permissive than iOS, is down 20%. Consumer spend has been more resilient, down roughly 8% in 2023, but a truer accounting is less favorable. After considering inflation, the real contraction is closer to 18%. Furthermore, consumer spend is only a portion of total mobile gaming revenues. Before the introduction of IDFA/ATT, roughly $3.50 in ad revenue was generated for every $6.50 in consumer spend. In 2023, this sum fell to roughly $2.50 (again, less in real terms). On this basis, total U.S. mobile gaming revenues are down something like 15% (23% in real terms).

Some have posited that the rise of game subscription bundles such as Xbox Game Pass, Ubisoft+, and EA Play have harmed spending on packaged games. The idea is that these offerings cannibalize $20–$70 purchases and reconstitute them into monthly (i.e., pause-able) subscriptions that cost $5–$17 per month and in some cases span hundreds of titles. As such, it’s possible for a user to skip a $70 purchase of, say, Starfield, and instead play it for $20 over two months, while also playing other games that they might otherwise have purchased, too. It’s also been suggested that the high price-to-value of these bundles also makes it difficult for purchase-only titles to sell at high prices. Proving or disproving this thesis is a challenge, but I don’t see the evidence that it’s actively reducing spending today (which also doesn’t disprove it).

With 25–30MM subscribers worldwide, Game Pass reaches no more than 20% of U.S. console and PC gamers. Microsoft Gaming revenue essentially tracks the overall market, so the clear evidence that Xbox’s business is being cannibalized is wanting. In the United States, PlayStation 5 has outsold Xbox S|X by 40% since 2020, more than twice the sales gap of the last generation of the two consoles; in 2023, the sales gap grew to 100%. It’s therefore difficult to argue that Xbox is cannibalizing its competitor’s business to float its own. Circana (née NPD) reports that subscriptions are only 10% of U.S. gaming revenues, and growth has stagnated year-over-year; were the value in subscriptions truly so high, one would expect a different arc. Furthermore, many of the top titles in game subscriptions, such as Destiny, Grand Theft Auto V, and Halo Infinite, have microtransactions. Accordingly, it’s not really accurate to say their inclusion in a subscription results in the full cannibalization of a player’s spending and/or prevents these titles from generating direct revenue. In fact, one might argue that by maximizing their player bases, some of these titles have a better shot of increasing their lifetime revenue (Palworld’s sales do not seem to be suffering from its inclusion in Game Pass). Certainly, this seems to be one of the major lessons of free-to-play gaming which, at least from my perspective, is more threatening to total revenues than subscriptions. FTP is the best way for a hit title to maximize its revenue ceiling (even PUBG, the fifth best-selling game of all time went FTP in 2022, and in doing so, hit new highs - as did Rocket League two years earlier), but such titles are now more than a third of console time and their extraordinary value makes it difficult for other titles (especially new franchises) to charge $70.

Of all the causes, post-COVID stagnation seems the most plausible. Circana reports that in 2019, 70 of every 100 of Americans played games, and those that did averaged 12.7 hours per week. In 2020, gaming penetration surged to 79 of every 100 Americans (+9), with average hours jumping to 14.8 hours per week (or +2.1 hours). In 2021, only 76 of every 100 of Americans were playing (down 3 YoY but still up 6 from 2019), but average weekly hours swelled to 16.5 (up 1.7 YoY and 3.8 from 2019) partly because less engaged gamers had stopped playing. By 2022, participation rates fell another three points (though still up three from 2019), but hours plummeted to 13 (up only 2% since 2019).

Gaming is not alone in its post-COVID regression. In 2019, ecommerce constituted 10% of total U.S. retail spend and 15% of addressable retail spend (that is, excluding products like cars and gasoline that face significant legal barriers to online purchase and in some states are prohibited outright). This share had grown in largely linear fashion from 3.5% and 6% since 2009, gaining 0.65 and 0.9 percentage points per year, respectively. As much of the United States locked down in 2020, ecommerce’s share surged to 17% and 23%. In 2023, ecommerce’s share was 15.5% and 22%, respectively, representing a loss of 1.5 and 1.0 percentage points over a three-year period. Remarkably, 2023’s figures are exactly where pre-COVID trendlines would have predicted. In other words, COVID did not permanently pull forward ecommerce penetration; it pulled society ahead of where it was ready to be, and so we stalled and shrank afterwards.

Still, gaming should be performing better than it is. Ecommerce as a percentage of retail spend may have gone sideways, but total ecommerce spend is up 27% since 2020 (11% after inflation) because retail spending has grown, too. The big hope for the gaming industry was that COVID would help expose gamers to more games, forge more player connections, and, most importantly, establish enduring new habits. It was obvious that as the pandemic ended and we went back to spending more time outside that more of our purchases would take place in person rather than online. But it was possible — I would have said likely —that video games would maintain their increased share of entertainment time and spend in the home, especially versus the dominant category, which is video. Instead, video has gained in both dollar terms and wallet share, ecommerce in the former but not latter, and games have lost in both metrics,

Gaming’s struggles likely stem from the often-ignored downsides of Metcalfe’s law. Gaming’s particularly powerful network effects mean that even marginal increases in the number of players can strongly impact all players’ playtime and spend. Put another way, if three of your friends play Call of Duty or Fortnite, not two, it’s far more likely you’ll play more often and for longer periods. The more people you play with, the greater the benefit from buying cosmetic items, too. However, Metcalfe’s law works in reverse, too — if a few friends stop playing or play less, you’ll probably play and spend less too.

Gaming remains a secular trend. The 140MM people born each year join a generation in which substantially everyone games and will see the end of this century, replacing a generation that was born midway through the last century and rarely gamed. Access to high-quality gaming devices continues to improve. Gaming culture continues to proliferate, and the art form of modern gaming continues to evolve at a rate no other medium can match. These are powerful tailwinds unlikely to slow anytime soon. Yet secular growth does not mean uninterrupted growth, significant growth, or profitable growth. And when a mature industry experiences a sudden surge of revenues, followed by several unexpected years of flat-to-down revenue growth but double digit growth in costs, all-the-while expecting revenues spend to rebound in the n+1 or n+2 year, etc., layoffs and cuts will eventually follow because aggregate P&Ls and title P&Ls will be wrong. But subscriptions, COVID, Metcalfe’s law, and IDFA are not sufficient explanations for why revenues are falling so short of economic averages, internal and external forecasts, and especially media comps (again, SVOD, movies, TV, books, music are all up, even with inflation), and layoffs so rampant and shocking. These explanations also don’t help us to understand what the years to come might look like or how growth might be restored. To do so, one needs to zoom out.

2024 and Beyond

Globally, the video game industry generated roughly $184B in 2023, down from $190B at its 2021 peak. Accounting for inflation, the drop has been even greater, with 2021 generating about $213B in 2023 prices, in which the market has shrunk $29B in real terms, or 14%. (The United States represents roughly 30% of worldwide revenues; China is at 23%.)

Over the last decade, the global gaming industry grew from $85B annually to $187B – an astonishing $102B in nominal terms, or +120%, and equivalent to an 8.2% CAGR. Adjusted to 2023 dollars, a still-incredible $76B was added over this period (+68% total for a 5.2% CAGR). In contrast, real GDP growth in the United States over this time was at roughly 2.3% compounded, while world real GDP grew at 3.0%. In other words, the industry spent a decade growing 1.7x faster than the world economy and 2.3x faster than that of the United States. Even if revenues were still growing, a slowdown from the last decade’s breakneck pace was bound to hurt. Yet that breakneck pace was very different depending on the individual segment.

Just under three quarters of this growth came from mobile, which massively expanded who could play games and how often gamers could play. Over the decade, mobile added $62B annually in real terms, for a CAGR over 10%. In contrast, the traditional gaming market (i.e., AAA console + PC) grew at a real CAGR of 2.8% (+$19B). Arcades, which were half of revenues in 1985, largely died over the last decade due to the rise of mobile, harming overall revenues (gaming giants such as Capcom and Konami have divested these businesses, though Square Enix continues to operate). VR has grown to $2–$5 billion since 2015, when the category did not exist. The dissimilarities in each segment necessitates individual reviews.

Virtual Reality

As the industry chart reveals, the clearest way to expand the gaming market is with a new device type. To this end, there are hopes that mixed reality will open up a new, large, and rapidly growing gaming segment. Since 2016, consumers have spent more than $10 billion on VR hardware, with software adding another $5 billion. Though these are large sums, software sales are now at $1B in ARR, and there’s a handful of popular and highly profitable VR games (Gorilla Tag, The Walking Dead, Beat Saber), the segment is still less than 0.5% of the global gaming industry (though probably around 1%–2% in the United States), and substantial growth seems unlikely over the near term.

According to IDC, worldwide VR/AR headset sales fell 8.3% in 2023, a year after sales fell 20.9%. The biggest drag on sales was the Quest 2, which sold roughly a million units a month in the year after its October 2020 debut but saw sales rates fall by more than two-thirds by its third year (the PlayStation 5 and Xbox Series S|X have sold at a relatively stable rate since November 2020). Some slowdown was expected after Meta unveiled the Quest 3 in May 2023 but set a fall release date, yet the Quest 3 appears to be selling more slowly than its predecessor. Reports suggest fewer than one in three Quest 2s are used on a monthly basis (points that harm both software and hardware sales). In February 2023, Sony released its PlayStation VR2, which boasted executive launch titles such as Gran Turismo 7 and Horizon Call of the Mountain, but nearly a year later, the device seems to be selling less than the original PS VR in 2016. Sony’s latest sales update for the PS VR2 was in May 2023, when it reported 600k in sales. The company has said little about the platform, or its content slate, since.

The Apple Vision Pro may help, but supply chain checks suggest fewer than 500k units are planned for sale this year, and Apple is not pushing the device as a gaming-focused one (there aren’t even Apple-manufactured controllers) but instead one for video-based entertainment, immersive calls, and workplace productivity.

Until there is sustained and compelling growth in VR/MR gaming, the segment will remain in a sort of chicken-or-egg stasis for game-makers. Major and indie publishers will not develop exclusively for the form factor (or even port their non-VR titles to it), which will hold back device sales, in turn constraining the market opportunity for publishers, and so on.

Mobile

While the 2022 and 2023 contraction in mobile gaming stemmed primarily from Apple’s IDFA/ATT and the post-hangover, the segment also faces deep structural challenges. Seventeen years after the first iPhone, there are not many new players for mobile devices to onboard to gaming, least of all high-ARPU players. TikTok, Reels, YouTube Shorts, and all the rest, meanwhile, are devouring much of the idle time once spent playing mobile games.

In part, although not just due to the above, the mobile segment has rapidly ossified. In the United States, as an example, the top three mobile games per genre generate roughly 40% of the genre’s revenue (range of 20-90%). 82% of revenue is held by titles over two years old (and over 50% is titles over four years old). Many categories are even more stodgy — the top three shooters are 70% of revenue and titles over 2 years old hold 94% share. In May 2022, EA launched a mobile version of its battle royale franchise Apex Legends, which had generated more than $2B in the 2.5 years since it had launched on PC and console. Only eight months later, EA announced the title would be sunset before its first birthday, having struggled to attract a player base that could sustain ongoing investment.

To understand this ossification, it’s helpful to break down the mobile gaming market into two (simplified) halves. The first half is made up of “casual” and “hyper-casual” titles such as Candy Crush or 8 Ball Pool — these are what most non-gamers and even some mobile gamers think of when they think about mobile games.

Though the “match-3” and billiards genres are fairly simple, market leaders such as King and MiniClip have spent more than a decade refining their gameplay mechanics — altering what’s a “swipe” versus a “tap” or a “press,” as well as how long or precise or often each interaction should be. The mixture of fundamental simplicity plus finely tuned mechanics leaves limited room for innovation — and even less for the sort of innovation needed to induce a player who has never played these titles before to try one or to steal a player from a rival title. This innovation must also be so fundamental that existing titles in the genre cannot rapidly clone the mechanic, either.

Many long-running titles have also built complex “meta” games atop the otherwise rudimentary main game. Examples might include unlocking digital items to create a virtual house or garden or collecting and customizing in-game characters, both of which create high switching costs, as they mean leaving behind years of progress in one title to start another title that, in all likelihood, is similar enough. For some users, it’s scary enough to leave behind a decade of leveling up — in 2024, the maximum level on Candy Crush Saga is nearly 15,000, with millions of players having crossed level 10,000 (at 4 minutes per level, a low assumption, that’s over 650 hours). On top of these challenges, and would-be insurgent must also have the budget and user economics to finance customer acquisition against entrenched rivals that likely boast greater cash reserves and, as fine-tuned profit machines, greater unit economics that enable greater ad spend. This dynamic explains not only the durability of seemingly easy-to-replicate titles such as Candy Crush in their genres but also their ability to defend against new formats as well. 2024 will be Candy Crush’s 12th year with 250–350MM monthly active users.

Though broadly defined “casual” games once dominated mobile gaming – and are still more than 70% of downloads – more than half of revenues and three quarters of growth now comes from “mid-core” and “core” and even “hardcore” titles such as Pokémon Go (technically casual, thought I doubt current players treat it as such), Roblox, PUBG, Call of Duty Mobile, and so on (for the sake simplicity, this essay ignores casino games, and includes simulation and driving titles in core). While core-and-above mobile games theoretically afford more opportunities for gameplay-based differentiation, they too have become competitively stale. Consider, as an example, the shooter category. The top 3 titles have 70% share of revenue, and 94% is held by titles over two years old and with brand equity that goes even farther back (e.g., 2017’s PUBG, 2003’s Call of Duty).

The causes of competitive stagnation in core/mid-core/hardcore mobile games are many and include some of the same issues facing casual titles, such as years of player lock-in, IP, and brand building as well as refinements in monetization and gameplay. A newer challenge relates to the fact that many mid and hard-core titles are cross-platform, now, too. This means that while they run on mobile and may generate most of their revenue there, they also operate on consoles and/or PCs. In success, such a release model maximizes network effects and total revenue but is far more onerous financially, creatively, and technically. Some titles, such as Call of Duty Mobile, are not fully cross-platform but instead support more minor forms of cross-play, such as cross-purchasing (buy a outfit in a console/PC version or mobile, use it on mobile or console/PC) or cross-progression (earn XP on any mobile or console/PC and progress on console/PC battle passes). These integrations make it even harder for new entrants to draw users away from existing titles.

As devices have become more capable, cross-platform games more common, and mobile gamers more experienced, the budgets for some mid-core and hard-core titles have become indistinguishable from higher high PC/console games. Two of the biggest hits of the last several years, 2020’s Genshin Impact, and 2023’s Honkai: Star Rail, spent at least four years in development and at their peak, had more than several hundred developers. Despite the lower cost of labor in China, where publisher miHoYo is based, the launch budgets for these titles ran $100-200 million each.

IDFA has also had a disproportionate effect on newer and smaller mobile game-makers and arguably strengthened the largest and most established publishers. The titles most able to build richly detailed user accounts (e.g. not just name and email, but age, gender, zip code, etc.) are those most proven or able to encourage users through in-game promotions, such as a free life or early access to next week’s level, etc. The utility (and targeting benefit) of an account system grows as a publisher’s portfolio grows. For example, a publisher which operates a series of titles (especially a series of titles with large player overlap) will have more information through which to target its players. These publishers can also use their network to grow each of their titles through cross-promotions (i.e. using excess inventory on Game A to recommend Game B, or through Game A paying their corporate sibling Game B for an ad rather than a rival Game C) and incentives (Game A users can get 3 free lives for downloading Game B!), and can do so in a highly targeted fashion (versus using poorly-targeted programmatic ads). None of these options apply to new game developers, or, really, smaller ones either. To this end, it’s notable that the two biggest new mobile games of 2023 were launched by and through two of the world’s biggest mobile publishers: MiHoYo used Genshin Impact to help launch its Honkai: Star Rail and Scopely used its network of titles such as Stumble Guys, Scrabble Go, Yahtzee with Buddies, and more. To return to downloads earlier, Sensor Tower reports US mobile gaming downloads have fallen roughly a quarter since IDFA while worldwide figures are down 6% (the delta is due to smartphone growth); the major mobile gaming networks are reporting only a fraction of this drop, with independents encountering severalfold greater hits.

AAA PC/Console

Nintendo is expected to release the sequel to the Switch in 2024, typically described as a “Switch 2” — that is to say, the device we already know and love but boasting 8 years of improvements in battery life, picture quality, and computing power. If so, it will doubtlessly break Nintendo’s boom-bust console pattern and be a large revenue driver in the calendar year. At the same time, the device’s ability to grow the market is less clear.

For example, the Switch 2 will partly cannibalize sales of the Generation 9 PlayStation and Xbox, which are likely to cost more than the Switch 2, too. In a way, the outstanding success of the original Switch — which is the third best selling console of all time — is also an impediment to its successor growing the market. Interestingly enough, the six-year-old Switch sold more units in 2023 than it did in 2017, the year it launched, or 2018 or 2019. It’s thus difficult to imagine the Switch 2 will, by itself, return the market to net growth. It’s similarly hard to imagine that in their fourth year, either the PlayStation 5 or Xbox Series S|X will suddenly hockey stick, or that PC gaming equipment will surge in 2024, either.

It's also critical to note that console sales have not grown as much as many imagine. Lifetime sales of Generation 8 consoles, which first launched in late 2012, are now 311MM – more than double that of Generation 5, which began in 1994. However, Gen 8 sales grew only 11% in the United States compared to a 15% increase in households (households that are also much younger than average and should be more, not less inclined to games than the average). A material, though not known portion of these sales also stemmed from mid-cycle upgrades (roughly 1 in 10 PlayStation 4 sales were of the PS4 Pro, many of which were bought those who already owned a PlayStation 4, with Switch Lite and Switch OLED at least one in three Switch sales) and replacement units (Gen 8 was the longest cycle in history, and the portable, kid-centric, and inexpensive Switch console was particularly prone to breakage). In addition, 83% of Gen 8 growth was Switch, yet roughly half of Switch games sales are of Nintendo’s own titles, and the platform sold 8.3 games per console, versus 12.1 for PlayStation (Xbox not known due to Game Pass), and at a 20-30% lower average price. The struggles of PlayStation (whose PS3 and PS4 have both fallen well short of PS2) and Xbox (which has never held more than a third of the console market, but usually ranges between a tenth and a sixth) also explains why there is now such focus on cross-platform publishing - most players are on other devices (including PC) and its no longer reasonable to bet you can attract them to yours, least of all in the tens of millions.

Towards the end of the last decade and start of this one, there was some hope that the market for “console-grade” gaming would grow as Google Stadia (2019), Amazon Luna (2020), and Microsoft’s xCloud (2021) enabled players to “rent” consoles in the cloud and play them on any device, rather than need to pay $500 upfront to play in their homes. I was always a skeptic (2019, 2020), and while progress continues (network latency is falling, broadband improving, data centers more numerous), cloud gaming adoption remains negligible (Google announced Stadia would close in 2022).

To grow hardware sales (or hardware-based sales, such as PlayStation 5 games), there must be great software to motivate such purchases. Unfortunately, 2024’s release slate looks grim. Not quite as rough as 2021 but certainly far weaker than 2023, which will make year-over-year growth tough (though the density of the 2023 slate will mean that many of that year’s top titles will instead be bought this year, albeit at lower prices). The Switch 2 is still a wildcard here — if the hybrid handheld-living room console does launch this year, it’s likely there are also some major, but not yet announced Nintendo games that will launch with it . Still, the paucity of 2024’s release slate is such that even a trio of new Super Smash Bros., Super Mario, and Mario Kart titles is unlikely to shore up the market overall.

Behind the console/PC segments stagnation – both in terms of hardware sales and software – is a more fundamental problem: renewal.

In the fourteen years spanning 2009 to 2022, the best-selling game in the United States came in only three varieties: Call of Duty (12 wins), Rockstar’s Grand Theft Auto (1 win with ten appearances in the top 15 in the ten years since its release), or Rockstar’s Red Dead Redemption (1 win with six appearances in the top 20 in the six years since its release). 2023 broke this trend, with Call of Duty falling to second place behind Hogwarts Legacy, which is based on the best-selling book series of all time. Due to the rise of free-to-play games such as Fortnite and Roblox, which do not “sell” but instead monetize exclusively through in-game sales, this list is increasingly flawed. Yet even with such inclusions, the point remains the same. Fortnite wins at least three years since its 2017 debut and charts in each of the other three, Call of Duty Mobile joins its PC/console peers in the top 10, Roblox is top 10 in at least five of the last years, while the mobile Pokémon Go boasts at least four of the last seven. The remaining best-sellers are mostly predictable: The most recent Mario Kart and Nintendo Switch or DS Pokémon, the annual release of online multiplayer titles such as FIFA, NBA 2K, and Madden NFL. The largest variety comes from a smattering of reliable sequels in the single-player offline category, including Spider-Man, God of War, Legend of Zelda, Pokémon, and Assassin’s Creed.

Of course, there are occasional insurgents in the top 20. In 2022, the brand-new franchise Elden Ring ranked 2nd in the packaged sales charts (and won Game of the Year at the Video Game Awards and DICE) and in 2020, Ghost of Tsushima ranked 9th — but they tend to be packaged, single-player offline titles and from established studios (and often, totemic IP, as was the case with Hogwarts Legacy, or Insomniac’s Spider-Man, which ranked 6th in 2018). The average playtime for these titles is typically 10–50 hours, roughly equivalent to 1.3–3.8 weeks’ worth of playtime.

Related Essay: Esports and the Dangers of Serving at the Pleasure of a King

Success with single-play, packaged, offline titles is, without question, still hard-earned and praiseworthy (four of my five most played games of 2023 were in this category). Yet it’s notable that, to the extent there’s a consistent opportunity to release a new top 20 games, the clearest opportunity is to produce a single-player title that can be a multi-week “snack” to 5-15MM players over a three-to-five year period – rather than one that can be a regular meal for hundreds of millions for three-to-five years. And this opening is probably best-suited for the existing category giants and existing IP (or in the case of Elden Ring, IP that is co-authored by George R. R. Martin). What’s more, odds are still scarce and worsening.

Though it’s based on the 2nd and 3rd highest grossing films ever and received solid reviews in its own right, Ubisoft’s 2023 Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora doesn’t seem to be on track to recoup its $120MM production budget (Barely a month after the title’s release, Ubisoft put the title on multi-week 33% discount on the PlayStation Store). A few months before Warner Bros. Games released Hogwarts Legacy, it published released Gotham Knights, another blockbuster-budgeted title that achieved weak reviews and sales. Two of Ubisoft’s 2021 AAA releases, Watch Dogs: Legion and Fary Cry 6, also disappointed (and may have lost money). Krafton’s 2022 title Callisto Protocol, which is believed to have cost over $160 million, also fell short of the publisher’s sales forecast, with Krafton downplaying the prospects of a sequel or updates.

A lot of the challenge here is economical. In addition to the aforementioned increases in costs per developer, the number of people needed to produce a AAA game have grown as publishers expand the scale and scope of their games —more and higher-fidelity cinematics with professional motion capture and vocal performances, greater environmental and enemy diversity, more thoughtful NPCs and side quests. The enormity of this effort is easy to measure, as is the output.

In the 1990s, an average AAA open-world title like 1998’s The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time for the Nintendo 64 might require only tens of megabytes, with the largest reaching 1–1.5GB (the 1997 PlayStation title Final Fantasy VII, which required three CDs to play). By the late 2010s, the smallest of these titles was 15GB and the largest would pass 200GB (2016’s Final Fantasy XV; the three-part remake of Final Fantasy VII, released from 2020-2028, is expected to be over 400GB combined). According to Nexon, one of the world’s largest video game publishers, the average tally of staff credits for an open-world action game has grown from roughly 1,000 in 2007 to over 4,000 by 2018, with costs growing 2.5x through that time (roughly 4x by 2024).

Insomniac’s Spider-Man is a great case study. The first title, released in 2018 for the PlayStation 4, is believed to have had a development budget around $100 million. The 2020 spinoff, Miles Morales, which had a higher-fidelity PlayStation 5 version, cost $156 million to make. 2023’s Spider-Man 2 is an epic leap over its already beloved predecessors — benefitting from a NYC map that covers not just Manhattan but also Brooklyn and Queens, and offering more than seven hours of mocap cinematics, and thrilling set pieces — yet its cost grew to more than $315MM (with a reported $40 million just for the cinematics). The first Halo, 2001’s Combat Evolved, cost $10–$20MM, whereas the 2021 version is said to have exceeded half a billion dollars.

Unfortunately, however, there has not been nearly enough growth in the number of AAA console/PC games, nor the average playtime or purchases from each user, to support these cost increases on an average basis. In many cases, even the top performing titles are struggling to make the math work. The first Spider-Man title sold over 22 million units, while Miles Morales sold 10-15MM. Early sales declines suggest Spider-Man 2 may fall short of both of its predecessors. And according to some reports, Insomniac has considered splitting up Spider-Man 3 into two $50 parts in order to address its $385MM budget. There are twice as many active Xboxes today as there were at the peak of the first Halo, but that’s a ways away from offsetting the 33x cost increase.

It’s common to hear that these titles could and should be made cheaper, but such reductions come at great risk in an environment with little growth and entrenched live services giants. Having released two Spider-Man titles over the preceding five years at $60 each, Insomniac needed to offer far more than just “more Spider-Man” for its $70 follow-up. And it certainly did. In fact, Spider-Man 2 helps demonstrate an ongoing challenge with the industry - packaged title prices are too low. Yes, there was just a $10 price hike for Gen 9 games ($60 to $70), but during Gen 5 and 6 in the 1990s, the typical came ran $40-60, or $76-115 in 2023 dollars. Not only have games become longer, on average, and more highly produced and capable, their real price has plummeted. And compared to alternative leisure activities (e.g. Buying a digital copy of an equally-good three hourlong Spider-Man movie or watching it in theaters, attending a concert, etc.), it is one of the cheapest forms of entertainment per hour and getting cheaper. Gamers hate the idea of paying more - and the success and quality of FTP games makes this harder - but they probably should be more expensive, if just to keep up with the price of the average good.

While increased fidelity (auditory, visual, performance, etc.) has increased cost by far more than it has expanded unit sales or revenue, these investments have become largely tablestakes. The original Last of Us was released in 2013, and even as a brand-new franchise, boasted an hour and half of full motion capture cutscenes and an original score from Gustavo Santaolalla, who had recently become the only composer to ever win back-to-back Oscars for Best Score (Brokeback Mountain and Babel). It’s telling, to this end, that the HBO adaptation, which was also scored by Santaolalla and repurposes his original work, makes extensive use of the game’s dialogue, camera angles, sets, and direction. The second Last of Us game, released in 2020, was over nine hours of cutscenes (Santaolalla also returned), and cost $220 million.

Not all titles need to emulate the Last of Us – a game famous for its cinematic quality and was not a pioneer, nor particularly well-known for its gameplay. Still, much though players might claim otherwise, expectations around visuals, the size and variety of an open world, the number and quality of side missions, the quality of character models and performances, et al, are set by these market leaders (which are often remade and remastered, thus resetting the bar in the years where there isn’t a sequel). It’s also worth stressing that many of these leaders, including The Last of Us and Spider-Man, as well as The Legend of Zelda, Starfield, Halo, are produced by the console platform – the business model of these titles is therefore not just their own sales, but driving adoption of console that then takes 30% of all other game sales. And the exceptions are, well, exceptional. CD Projekt Red spent $436 million on Cyberpunk 2077 and its DLC expansion – a budget possible only because it followed up CDRP’s The Witcher III, the 8th best selling game of the last 25 years, and because CDPR is based in Poland, where developer salaries are roughly 50% cheaper in USD. Many publishers have (or will soon) laid off employees so that their roles can instead be outsourced to a (much cheaper) foreign work-for-hire services studio. Indeed, there is a growing consensus that to make the games (or sequels) that players demand, it’s no longer possible to be a purely domestic and/or employee-based studio. Some are even moving to a model where key art and level design are managed in high cost markets, but with levels and models built abroad.

And brutal though single-player games have become, it’s particularly hard to launch a large live services title – one that can sustain hundreds of hours of play each year and year-after-year, and is by far the largest opportunity in gaming.

Over the past decade, many of the most notable efforts to launch a new live services giant were cancelled prior to launch, such as Cyberpunk 2077 Online and The Last of Us: Factions (scrapped after the enormous success and the related sales boost of the TV adaptation). Several others were shuttered early despite their original success. Rockstar’s Red Dead Redemption 2 is one of the five best-selling games over the last quarter century, but the final update to Red Dead Redemption Online came only 20 months after its launch in November 2019. Rockstar’s GTA Online is still topping the charts 122 months after its debut. The Nintendo Switch is Nintendo’s second best-selling console and Animal Crossing: New Horizons, launched at the height of COVID, is the platform’s second best-selling title. Yet Nintendo was not able to (or not interested in) sustaining ACNH (the last update came only a year and half after the game’s debut despite the fact it sold 3x as many copies as its predecessor).

In February 2019, BioWare, the EA-owned studio behind Mass Effect, Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic, launched Anthem, only to announce a year later that updates would be “paused” so that BioWare could “substantial[ly] reinvent” the game. A year after that, Anthem development was terminated. In August 2020, Ubisoft launched Hyper Scape, the company’s take on the still red-hot battle royale genre. Two months later, Ubisoft announced the game was “not able to achieve” expectations and would be overhauled so that it could “reach its full potential.” In January 2022, Ubisoft announced the title was shutting down.

A month after the debut of Anthem, Square Enix launched The Avengers, the first AAA adaptation of the (still at its peak) super-franchise since the Marvel Cinematic Universe began in theaters in 2018. Unfortunately, the title never broke out and Square Enix called it quits after 2.5 years.

In July 2021, Splitgate, a sort of Halo-meets-Portal shooter, launched its open beta across PC, Xbox, and PlayStation, amassing 600,000 downloads on consoles within a week and 13 million over two months. The initial success of the title landed 1047 Games a $100MM investment at a $1.5 billion valuation in September, led by Lightspeed Venture Partners. A year later, 1047 announced it was ending development of Splitgate (with the title remaining online) to instead build an “entirely new shooter” — an effort that is likely to take years.

Amazon’s $200-500 million MMORPG, New World, launched to considerable audiences in September 2021 – peaking at nearly a million concurrent users and an estimated 10-15 million in its first 30 days. Three months later, players were down 96%, and two years later, it has more than halved again. Today, the game averages roughly 300,000 monthly players – a still substantial sum, but far from one which earns its initial budget or justifies substantially ongoing investment.

In July 2022, Warner Bros. Games launched MultiVersus, a brawler based on its parent company’s IP (think Super Warner Bros.) Though the title was technically in “open beta” and free-to-play, players could purchase in-game characters, battle passes, and even “founders packs” — and did so in great volumes; MultiVersus topped sales charts in its launch month and ranked 5th a month later. By its third month, Warner Bros. Games announced over 20 million had played the game, which won Best Fighting Game of 2022 at the Video Game Awards in December of that year and the same award at March 2023’s D.I.C.E. Awards. But then Warner announced that the game would be taken offline for at least a year in order to apply learnings from the “open beta.” Early signals suggest that Suicide Squad: Kill the Justice League, which has been in development since at least 2012 and is Warner Bros. Games first big release after Hogwarts Legacy, will also struggle. In 2023, Bethesda published the live services-aspirant Redfall, but received brutal 53% and 56% Metacritic score for the PC and Xbox editions of the title, and even lower user scores. The business case for further investment is hard to see.

Overall, there has been only one new AAA live services titan in the West over the past several years — partly because there have been no major breakthroughs in game tech or play. 2016 had Pokémon Go, but there have been no hit AR titles since. 2017 saw the emergence of the battle royale genre, which has become the biggest AAA game genre in history and has led to the creation of PUBG, Fortnite Battle Royale, and Free Fire (all 2017), with Call of Duty Mobile and Apex Legends following in 2019 and Call of Duty Warzone in 2020. The one exception is Genshin Impact, a free-to-play AAA cross-platform title released in September 2020 and made by the Chinese developer-publisher miHoYo. Genshin generated over $3 billion in its first year (more than any other title in history with the possible exception of Fortnite), with roughly a quarter of its revenue generated in the United States. In a matter of months, Genshin proved that Chinese game-makers had mastered AAA gaming, free-to-play gaming, Zelda-like open world gaming (and quality), and worldwide blockbuster gaming. Notably, however, the majority of Genshin’s revenue is generated from players in Asia, on mobile devices, and through gambling-style “Gacha” mechanisms (e.g. loot box mechanics) that are sometimes illegal, widely looked down upon, and now rarely used in the West.

The underlying challenges facing live services titles are the same as those facing single-player packaged ones – but far greater. After all, such a game is not trying to be a brief snack, but to change a player’s diet altogether, which means contending with all current live services titles, rather than just the few packaged titles released in and around the same time. More challenging still, this game must all change the diets of the player’s friends. Even if a publisher produces, in a simplified sense, a Game 4 of 10 friends prefer to the one they presently “main,” their experience playing that Game is nevertheless inferior if their six friends don’t come over. As such, this new game will struggle to retain the four it once attracted - and overall, those four users probably find that most of their needs and wants are already met by the games they already play and which keep being updated, too.

Retention, not acquisition, is ultimately the real contest for a live services game – and the volume of content that is needed to sustain ongoing play is substantially higher than 5-6 years ago too. This isn’t just volume of cosmetics, but the underlying content players consume too, map updates, missions, weapons etc., and their velocity, too. It’s financially impractical for smaller-sized publishers and studios (e.g. 1047 Games) to have a large live services operation (people, plans, infrastructure) ready to go when their game launches - even though they naturally hope for a blockbuster open or at least second-base hit. Even after a game breaks out, it’s risky to staff up as these investments are predicated upon retention curves that have not yet been proven, while competing with entrenched giants that boast hundreds or thousands of (profitably employed) developers, larger and more stable user bases (and thus stronger network effects) and consider lock-in (Fortnite players have spent at least $20 billion on avatars only available inside its ecosystem – investment that is hard to leave behind). Many games, such as Square Enix’s The Avengers, have been able to sustain a decently sized player base (hundreds of thousands of users), but not enough to justify ongoing investment.

More recently, the brutal upfront cost to AAA game development and requirements of ongoing support has forced many publishers to shift away from free-to-play releases and instead focus on traditional packaged sales. The former model substantially increases a title’s revenue ceiling by expanding its potential player base and reducing friction to customer acquisition, but it also lowers the title’s floor to near zero. Premium sales, conversely, have a lower ceiling and higher floor that’s also easier to predict based on awareness and pre-orders, and also provides the publisher more time to fine-tune microtransactions and live services monetization, after which they can (and often do) go FTP. FTP also doesn’t fit all titles equally well, either, as cosmetics (and IP mashups) fit a title like Fortnite better than, say, Tom Clancy or Battlefield, and non-cosmetic purchases can easily distort the game’s fairness.

Lastly, growing costs and declining odds has also made it difficult for any large game publisher to bet on new IP (there’s no joy in detailing the failures here, so they’ll not be mentioned) or even gameplay styles. Upon cancelling its multiplayer version of The Last of Us late last year, Naughty Dog issued a press release containing the following explanation: “In ramping up to full production, the massive scope of our ambition became clear. To release and support The Last of Us Online we’d have to put all our studio resources behind supporting post launch content for years to come, severely impacting development on future single-player games. So, we had two paths in front of us: become a solely live service games studio or continue to focus on single-player narrative games that have defined Naughty Dog’s heritage.”

Playing the Hits

That there is no new revenue titan is not to say there aren’t new and profitable titles and franchises. $185 billion a year, even with limited growth and turnover, is still a lot of opportunity. Riot’s Valorant, which was released in 2020, is up to 28MM MAUs – more than its 2021 average. And Nexon/Embark’s The FINALS, which debuted in December 2023, could be the next blockbuster cross-platform competitive shooter. At the same time, both titles are exception cases. Riot is owned by the world’s largest video game publisher, Tencent, operates one of the five most popular games in the world, League of Legends, has over 4,500 total employees, and is one of the few companies in the world that successfully self-distributes its games on PC. Nexon is another one of the world’s largest gaming companies, having produced several multi-billion dollar franchises including KartRider, MapleStory, and Dungeon & Fighter, and though its CEO has long argued against $100 million dollar budgeted games, has declined to share The Finals’ budget, or whether it exceeded that threshold.

It’s also not clear that either title has expanded the gaming market, rather than taken share from other shooters (including the two-decade-only Counter-Strike: Global Offensive). Shifting users and monetization between games (as with older to new generations of consoles) isn’t growth, it’s just movement. And part of what has made Valorant such a great shooter is also what constrains its revenue and player-base: it can only be played on PC. The Finals is cross-platform, though a substantial portion of its playerbase is in China and it is showing early signs of significant retention and monetization challenges. In January 2024, Nexon announced that Warhaven, another free-to-play multiplayer live services title published by the company and released in September 2023 , would be shut down. "To create a game that could be cherished and enjoyed over an extended period, we invested much consideration and effort,” Nexon said, “Despite all the shortcomings, we will deeply cherish the warm affection and support you have sent towards Warhaven in our hearts. Thank you for being part of Warhaven's journey."

Among Us, first released in 2018, was an explosive success during the pandemic — passing 500MM lifetime players, peaking at 3.8MM concurrent users, and averaging more than 200,000 concurrent users in all of September 2020 (up from only a few hundred three months earlier). Yet lifetime revenue for the title is estimated at $100–$200MM — an outstanding sum for InnerSloth, the game’s developers, which had fewer than a dozen employees — but marginal at the industry level. But the magic didn’t last: by June 2021, users were down 95% and have halved again since.

I want to be clear that there have been many indie successes over the last several years — Hades, Valheim, Dave the Diver, Stardew Valley, Cocoon, etc. But it’s worth returning to the opening from this essay: nearly all of the hits of 2023 are sequels, remasters, updates, or remakes. The title most likely to displace last decade’s biggest hit, Grand Theft Auto V, from the sales charts this decade is likely to be Grand Theft Auto VI, due in 2025.

And most of the big, new efforts from the major publishers? They seem likely to financially disappoint – and the few titles that thrive are unlikely to cover the failures. This observation is behind a great deal of the layoffs of 2022, 2023, and now 2024. The major game-makers are profitable, some have even seen greater profits in each of these years. Yet faced with rising costs and lowering prospects of success, they are now “rationalizing” their portfolios. In some cases, this is being more realistic about whether a current title can grow or even sustain its current userbase, and reducing staffing accordingly. In particular, though, publishers are scrutinizing their pipeline of titles in active development and their incubation projects, too. Many would-be games are being shutdown as a result, which leaves talented developers, artists, and testers without a P&L - and at a time when other games at the same company are being shutdown or scoped back for the very same reasons. There are now fifteen studios at Activision supporting the Call of Duty franchise.

Venture Crash

Nearly all media categories face growing concentration of revenues around a few major content-makers and franchises. Yet the uniqueness of games – their stronger network effects, longer runtimes, ability to be updated, ability to price discriminate to the point many users might generate $0 in revenue but others tens of thousands per year - makes the category far more insular, even though it requires no intermediary distributor.

It would take 70 hours to watch the entirety of Game of Thrones – half of the average American’s monthly TV time. The average Fortnite player spends forty hours a month playing Fortnite… and has been doing so for years. There are constantly new musician artists rising to prominence as generations turnover, artists age or come of age, and new writers or sounds emerge. Movies spent barely five years dominated by Marvel and other comicbook films – but not as long as many imagine – and during that time, many other franchises ascended and hits were launched, too. Due to the volume of TV that’s watched each year and the length of the average season, there are constantly new hits in the category, too. Books are even more permissive.

Gaming’s ossification creates a vicious cycle – studios don’t take (or are sometimes punished for) risk-taking, which means less innovation in mechanics, and less likelihood of expanding the market by appealing to new gamers or increasing engagement from occasional ones. Capcom is the best example of this dynamic – while many of its competitors struggled to build new IP or adapt old IP to live services, Capcom has thrived specifically because it has focused on single-player titles (and in large part, remaking its old hits). But eventually, those remakes run out, and rarely do they expand the market.

Many of the challenges above are reflected in the funding of video gaming startups— funding that, in theory, should help create the next disruptive gaming startup, platform, or game mechanic. During the pandemic, as gaming revenues, playtime, and player bases surged, so too did the category’s venture funding. Not only did it become easier for gaming VCs to raise substantial funds, but many non-gaming funds began investing in gaming companies, too, after seeing those hockey sticks profit curves and fielding calls from LPs wondering why their investment dollars weren’t participating in said growth. The consequences have not been great.

A lack of sector experience and rush-for-sector exposure has led to bloated rounds that have made subsequent fundraising efforts difficult for startups, while also encouraging bloated cost structures at these same companies, and diluting already-scarce talent across many more (and statistically doomed) startups. Worse still, the abundance of funding did not produce new hits. There are some solid new studios and titles, but VCs are in the business of home runs, not doubles, and there just haven’t been any. Which makes sense: insurgent startups are hard to build in low-growth markets with stagnant sales charts. The result is a crash of funding.

Overall venture funding in North America is down 51% from 2021 highs, but still up 15% from the 2018-2019 average. In contrast, gaming has contracted 77% from the high and is down 28% net from 2018-2019 average. And while overall venture funding has stabilized, gaming is still contracting. The result is clear and unavoidable: there will be many, many gaming start-up closures over the next two years — as they will be unable to raise capital and thus complete the games they’ve begun (and probably budgeted too high). This sucks. It is historically new gaming studios that crack a new mechanic, be it battle royales via Brendan Greene (or the independent Minecraft mod Survival Games), AR/LBE via Niantic, MOBAs through DotA, and so on. The spectacular success of Palworld quite obviously reflects a decade of gamers frustrated that the Pokémon franchise remains exclusive to (lower powered) Nintendo Switch and has seen such limited innovation in overall gameplay, multiplayer functionality, and genre (Don McGowan, the former but long-time Chief Legal Officer of The Pokémon Company, told Stephen Totilo “[Palworld] looks like the usual ripoff nonsense that I would see a thousand times a year… I’m just surprised it [hasn’t received legal notices by now].” Such innovations are needed if the gaming industry is to grow who participates and/or how much they spend. (Incredibly, Palworld-maker Pocket Pair does not seem to have raised any venture funding - more on this later).

Hope to Play

That gaming will return to growth is without question. What’s less certain is whether, how, and when it might grow above core economic growth or population growth rates; and whether, how and when it might advantage upstarts, rather than further insulate the leaders, and the impact it might have on industry jobs, too.

It’s clear, for example, that transmedia will become an increasingly essential part of any franchise strategy. Historically, such an expansion was an afterthought or nice-to-have. In theory, a hit film or TV adaptation was “good for the brand” and made both existing fans and internal team members feel good. Yet the economics to the licensor were modest (Nintendo profited so greatly from The Super Mario Bros. Movie because it also financed half the production), the distraction and risk high, and their core business continued to hum. However, gaming sales have stagnated just as Hollywood interest in gaming IP has piqued, and with it, interest from the best of Hollywood’s writers, directors and stars. Meanwhile, consumers continued to reiterate their desire for such content - and their willingness to then “play the game,” too. As audience attention becomes evermore scarce, the importance of adaptations will only grow - and while this strategy is available to all game-makers, it naturally advantages the larger players whose IP is most popular and long-running, and who can afford the distraction such an adaptation might bring and the financial investment to maximize their upside.

The dynamics in subscription are similar. Game-makers big and small tend to dislike subscriptions because they inherently build up value (and patronage) for a distributor, while capping the content-makers own upside (a reversal of a 20-year trend in the other direction). Providing younger, less capitalized start-ups with a lower risk distribution model (i.e. licensing fee versus the need to gamble on free-to-play or packaged releases) that also drives greater engagement is probably important and additive, not harmful. These deals will sometimes fall short of development costs, but they can help a high potential team and new franchise to safely reinvest in live services and/or sequels that might do much bigger business. If Game Pass and Netflix can grow the playerbase for Grand Theft Auto V a decade after it releases and following more than 190MM in unit sales, these services can probably help a would-be GTA1.

Over the past 5-10 years, most of the “big” game-makers strategically prioritizing free-to-play live services (which did not play to their strengths, as the results often proved) , producing remakes (profitable, but less likely to expand the market), and franchise sequels (same), gaming innovation in games has mostly been through scope/scale, or limited to A/AA studios making packaged games. I’m optimistic that a renewed focus on “boxed product” by these same studios will aid margins, encourage risk-taking, and also offer betting publishing deals to younger studios. Furthermore, a side-effect of Big Gaming’s multi-year focus has actually been a wider opportunity for these A/AA studios, many of which have now produced several titles but maintained their low cost structures and improved their ability to work as a team (Palworld is Pocket Pair’s fourth game since 2018). The market is also now on the cusp of many accomplished “UGC platform developers'' (i.e. Roblox developers) shifting to standalone titles. Lethal Company, which debuted in October, has grossed more than $120 million and was made by a single 21-year old developer that started on Roblox at the age of 10, and shifted to itch.io and Steam by 14. The capabilities of A/AA games also continues to grow as game engines such as Unity and Unreal improve, and their asset stores, which make millions of items such as a car, house, or pig, available to license at low cost, expand in quality and size. These smaller studios will continue improving and eventually, the industry might look back at the last 5 or so years and see it as a temporary period of competitive stagnation that quickly and emphatically reversed. At the same time, the success of many of these developers is typically rooted on the use of asset stores and foreign/outsourced labor that, as a result, is unlikely to bring many jobs back to Western markets. The reported budget of Palword, less than $7 million, is a testament to how few high paying jobs these hit games might afford. In addition to extensive use of asset stores, most experienced game developers have concluded that much of Palworld’s design and programming work must have occurred through low-cost contractor work in markets such Central America and Malaysia.