Netflix and Video Games

In 2018, I released the third entry in my “Netflix Misunderstandings” series: “Netflix Isn’t Being Reckless, It’s Just Playing a Game No One Else Dares.” In it, I argued that while Netflix was unlikely to pursue live sports, live news, or ads for “at least a decade,” a nearer-term push into gaming felt inevitable given the company’s culture and growing scale. Later that year, I tweeted that “Fortnite is Netflix’s most threatening competitor.” (41 days later, Netflix CEO Reed Hastings mentioned Fortnite for the first time, writing in his Q4 2018 investor letter, “We compete with (and lose to) Fortnite more than HBO.”)

The language in my tweet was deliberate. Fortnite isn’t Netflix’s largest, primary, or most day-to-day competitor. That’s clearly Disney, followed by HBO Max and probably Amazon Prime Video. But Fortnite, as an instantiation of social gaming, is Netflix’s most threatening competitor. (Obviously, the tweet was being deliberately provocative, too).

Three years later, Netflix has “officially” entered gaming. During the company’s Q2 2021 earnings call, Hastings confirmed Netflix had hired its first-ever VP of gaming, and also began to unveil how the video streamer would enter video gaming. Q2 2021 was notable for a few other reasons. For example, it was also Netflix’s worst-ever quarter in terms of subscriber growth. In the United States and Canada, the company lost over 400,000 subscribers combined (this was only the second time UCAN shrunk, with the company losing 126,000 in Q2 2019). Internationally, Netflix had its smallest increase in subscribers since 2014 (1.5MM). During the second quarter, Disney’s streaming business (which spans four different SVODs and therefore includes some double/triple counting) reached nearly 175MM subscriptions. This meant the gap between Netflix (210MM) and its next closest competitor had also reached a new record low.

This doesn’t sound like the time for the famously focused, streaming “OG” to expand into video gaming. And while it’s common to hear that “gaming is now four times the size of the global box office,” the box office is less than 1/15th of total video revenues globally. In other words, gaming is likely to be ~$180B in 2021, while video will exceed $650B. There’s a lot of headroom left!

With this in mind, and as someone who previously helped operate several SVODs and now invests in and produces games, I thought it was time to revisit the topic of Netflix and gaming. This essay will cover four areas: (1) Why Netflix wants to enter gaming (beyond the money); (2) The challenges Netflix faces when entering gaming; (3) What Netflix seems to be doing; and (4) Where this might be going and when.

#1: Why Netflix Wants to Enter Gaming (Beyond the Money)

For years, Netflix has identified its competition as “leisure” at large:

“As discussed in our Long-Term View, we compete with all the activities that consumers have at their disposal in their leisure time. This includes watching content on other streaming services, linear TV, DVD or TVOD but also reading a book, surfing YouTube, playing video games, socializing on Facebook, going out to dinner with friends or enjoying a glass of wine with their partner, just to name a few.” - Netflix IR

The focus on leisure, rather than “premium video,” is important. Economists usually define leisure in contrast to two other uses of time: work and necessity (e.g. eating and sleeping). And to that end, Netflix has tweeted “Sleep is my greatest enemy” and doubtlessly hopes you’ll stream while you eat, too. Lots of folks also use the service while using the restroom, another necessity.

In recent years, most of the entertainment industry has adopted Netflix’s mental model. In 2019, Nintendo of America’s President said, “That time you spend surfing the Web, watching a movie, watching a telecast of a conference: that's all entertainment time we’re competing for. [Nintendo]’s competitive set is much bigger than [its] direct competitors in Sony and Microsoft. [Nintendo] competes for time.” In the last six months, Snapchat and Spotify have both identified Fortnite as a key competitor.

“Job-to-be-done theory” isn’t new. Marketing myopia is a decades-old term referring to the tendency of a business to define its competitive set too narrowly as a result of thinking about the products/services they sell not the function they fulfill. If one says “we’re a train company” or “we’re a petroleum company,” not “transportation” or “energy,” they’re likely to miss the opportunity, threat, and importance of busses and solar.

Hollywood’s newfound focus on “attention competition” reflects a fundamental, and relatively recent change in consumer behaviors and options.

For decades, the key decision for consumer leisure was essentially “what to watch.” After all, video was the most dominant entertainment category. And by far. In the United States over 90% of the population watched TV each day and for an average of 5.5 hours. The next closest media category was audio with 2.5 hours per day, nearly half of which takes place during commutes and a quarter of which is done while working. In this regard, it’s not fair to say consumers “pick” audio half as frequently as they do video. Rather, they mostly pick audio to complement another activity they have to do. When given the choice between various content categories and without constraints, most humans have picked video.

It has been obvious for years that on demand streaming will become the dominant access modality for video. And crucially, streaming shifted the question from “what to watch” to “where to watch.” This, in turn, created the “Streaming Wars,” rather than just nightly or season-specific battles for ratings.

In the linear Pay-TV era, consumers picked a specific show/film after channel surfing through the bundle feed or consolidated programming guide. And almost every network and media company was part of this bundle, and they were rarely (if ever) dropped. As long as a household had Pay-TV, essentially everyone was getting paid and every competitor (if that’s even a fair term when sold together) could acquire a viewer with the click of a button (accidental or not).

This isn’t how streaming works. Instead, services are predominantly sold and accessed separately. As a result, viewers start “streaming” by first picking a service to watch, then finding a show on that service. This has a few observed implications. For example, a household only subscribes to an n+1 service if they run out of content to watch on services 1-to-n, which means Service A might have four times the subscribership of Service D. In addition, a user will only switch streaming video apps if the app they’re currently surfing lacks anything they want to watch, which means services with equal reach might have very unequal usage. Given SVOD is a predominantly fixed cost business and audiences are definitionally required to have a “hit,” we therefore have the “Streaming Wars.”

For years, Netflix was uncontested in “where to watch.” When it launched in 2007, the only direct competitor in the United States was Hulu, which had no Originals and even now has a modest Originals budget, and there was no major challenger abroad. YouTube was a global service, but it served a different type of content that, even for younger audiences, was a minority of total video consumption. YouTube’s efforts to expand into premium video didn’t work whether it was via partnerships or Originals.

Netflix always faced a Catch-22 in streaming - if indeed it would become the dominant access modality for video, then more competition would come. Otherwise who cares. Clearly, Hastings was right.. and fourteen years after launching an SVOD service, his company now faces a dozen competitors, rather than one. Despite this, Netflix still wins the question “where to watch” more than any other service. And while continuing to win isn’t easy (attract great creatives, make great content), the roadmap is relatively clear.

The most threatening problem for Netflix is the generational changes that are making “where to watch” the second question, not the foundational one. For hundreds of millions, the question is now “what to do.” Leisure, in other words, defaulted to TV for decades. It no longer does. This means that fighting for leisure time via video means losing share one way or another. And it’s likely this share is lost to gaming.

Every generation plays games more than the one that preceded it. Generation Y games more than X, Z more than Y, and Alpha more than Z. Everyone born today is a gamer, which means there are 140MM new gamers every year. And every year, more games run on more devices, at higher quality visuals, with greater capabilities and more sophistication. Every constraint is relaxing.

The most important might be the very definition of “gaming”, which seems to be devouring all other forms of media. Is a Fortnite concert a concert? A video? Is it streaming music? What if you watch a short-film inside Fortnite? Or a live event? Or walk a museum inside of it? What is Twitch? Or VR Chat?

Gaming’s growing strength in social experiences also makes it harder for video to be better. You might prefer watching Netflix Series A versus playing Call of Duty: Warzone, but not when your friends are playing (which is increasingly likely). Metcalfe’s Law more strongly affects a multiplayer game than even the most social TV series, such as The Bachelor.

Then there’s efficiency. Simply put, the entertainment industry has never seen a content category that generates greater “time leverage” than a hit video game. Netflix has 12,000 employees and relies on scores of contract workers and partner employees for its productions, and spends over $20B per year on its content (most of its competitors are $10-20B). Among Us was made by four developers and hit 500MM MAUs in November 2020. PUBG launched with 70 developers in 2017 (it’s now supported by 500) and reached over 150MM peak DAUs in 2020. Fortnite launched with fewer than two dozen developers, and while it has over a thousand today, total annual operating expenses are less than $1.5B even though it generates $4B+ per year and delivers three billion hours of entertainment per month across its 70MM MAUs.

All of this is possible because video games are a platform for multiplayer storytelling, rather than a linear narrative. Fortnite has only marginal changes each multi-month season, but the reliance on “your friends” and unscripted narratives means that a player can spend dozens of hours satisfied. The Office is highly rewatchable, but over its nine-year run, it produced less than 75 hours of unique content. Game of Thrones ran for eight years and produced the same.

Not only are hit games SVOD-sized in their reach and impact, but they’re inherently “D2C” too. Although most gamers access a title through an intermediary, such as Xbox or the App Store or Steam, each of which operates their own player networks, most game publishers also deploy their own account systems and collect troves of user data. This is different from video. While Netflix is elevating Formula 1’s brand and fandom Drive to Survive, it isn’t literally building an F1 ecosystem, player database, or D2C offering. And Netflix is the exclusive distributor of Drive to Survive. When you play Call of Duty Warzone on Xbox, you’re using an Activision account and can access the title and your entitlements on several other platforms.

Netflix can defeat NBCUniversal’s Peacock or crush Lionsgate’s Starz in the streaming wars, but even if it were a successful video game publisher or platform, the dynamics mentioned above mean that new media brands, giants, and ecosystems will continue to emerge in gaming. And Reed Hastings says Netflix competes with everyone one of them.

As these companies grow, their ambitions will evolve. After all, they’re all in competition for time. Two years ago, Fortnite’s multimedia efforts were essentially limited to marketing integrations (i.e. Batman skins and miniature Gotham inside its battle royale map), debuting movie trailers, and hosting one R&D-focused virtual concert annually. Today, the team is writing crossovers into DC’s physical comics, hosting film festivals, and operating an ongoing concert series. And Epic has stated that its goal is to allow all IP owners and companies to build on top of its platform to the fullest.

Riot Games licensed its internally-produced anime series Arcane to Netflix for distribution, rather than take on these duties themselves. However, it’s hard to imagine this being Riot’s long-term preference. If Riot is successful building a “new Disney” - something the company hopes Netflix’s reach will facilitate - will it still look to outside partners in a decade? I’m doubtful.

After all, this current model means asking LoL fans to leave the Riot ecosystem, and potentially sign-up and pay for a competing one, in order to access League of Legends content. It also means Riot is sharing responsibility for franchise marketing, losing out on most user/engagement data (and certainly the ability to connect this with player data), and relegating Arcane to be promoted/placed alongside many other franchises, some of which are based on competing games. And Riot doubtlessly plans more TV series and films, which means it must either sell those to Netflix, thereby making Netflix the “second hub for LoL,” or fragment these adaptations across many services, which would frustrate fans and make it harder to build a cross-media universe. This is obviously suboptimal.

Related Essay: Why Gaming IP Is Finally Taking Off in Film/TV

To this end, it’s notable that Netflix is adapting more gaming IP to film and TV than the rest of its competitors combined. This focus makes sense. The majority of film/TV/book IP is owned by Netflix’s video competitors (e.g. Disney, Warner Bros., Paramount), and therefore inaccessible to Netflix. In gaming, the streamer has a wide range of titles to choose from, many of which are globally popular and decades old, as well as suppliers who don’t resent Netflix’s success and aren’t planning their own competitors. But in an era of “competition for time,” where every company is an “entertainment company” (rather than a movie studio or game maker or a podcast studio), and the most valuable content in the world are franchises, this may be a dangerous long-term bet. No IP owner wants to send their customers, creative, or IP to a third party.

This issue extends to Netflix, in fact! Gaming has become a critical channel for creating new IP, telling stories with existing IP, building love for any IP, and monetizing that love, too. As a result, Netflix must participate in the category if it wants to develop or grow its franchises. But today, that means Netflix must outsource almost all of this experience. In other words, Netflix must hire a competing entertainment company to produce content that it can’t run, and which distracts its consumers away from video and towards a competing entertainment platform.

#2: The Challenges Netflix Faces When Entering Gaming

The elevation of the leisure question from “what or where to watch” to “what to do” is a challenge for Netflix. It’s hard to compete with Disney+, but the playbook is clear, Netflix knows how to do it, and both services operate in the same category. Gaming isn’t just different and new, it’s also particularly hard for Netflix to enter.

As I detailed throughout the Netflix Misunderstandings series, Netflix’s success had a number of drivers, such as its aggressive and underestimated spending, excellence in product and technology, unique (but correct) hypothesis on the future, its approach to series marketing, and the reluctance of its competitors to disrupt their business models (and corresponding willingness to license out their best content). Today, most of these advantages have been reduced or eliminated altogether. In video gaming, none apply. And the collective consequence is profound.

Technology

It would be relatively easy for Netflix to set up a streaming music or podcasting application, or a book service. Gaming, however, requires many new, difficult, and costly technologies to be built.

For example, the most popular and lucrative games in the world are online and multiplayer. This requires Netflix to create and operate extensive (and highly social) player account systems, including matchmaking, leaderboards, and entitlement/achievements management services, as well as live talk and text, anti-cheat systems, customer support, microtransaction payment, update/patch management, and more. Netflix has none of this technology today - not even basic scaffolding for it. And this technology requires substantial title customization, too, unlike video files. Netflix could outsource parts of this stack to Amazon Game Tech, Microsoft, Discord or Valve or Epic Games, but this is an even larger strategic, technological, and cultural shift. Yes, Netflix uses AWS and Akamai, but it doesn’t outsource the operation of consumer-facing, monitoring, and managing systems. If and until Netflix builds these capabilities, it can only pursue only the smallest segment of the gaming market: non-competitive single player titles.

Then there is the technology for distribution. It makes no sense for Netflix to make a physical console. As a result, its games must be locally run or cloud streamed. The former has several challenges. For example, over two thirds of Netflix consumption takes place on televisions. Yet, almost none of these devices (including connected TV boxes like Apple TV or Roku) have the physical components or SDK/APKs required to operate and deliver AAA games. Some could support lightly casual games, but not with touch, and it’s worth noting that Apple TV cannot run Netflix branching narrative titles, such as Bandersnatch. Consoles, of course, can play almost all games made today. But none will allow third party platforms to operate. This means Netflix can’t aggregate third party content (as Microsoft Game Pass). Instead, it must launch its own standalone games (like any game publisher) or launch a bundle of its own games (as some game publishers, such as Ubisoft and EA, do).

Netflix can operate locally installed games on mobile devices, but it faces many limitations as a result of OS/store policies and hardware. For example, Apple does not allow any apps to include a bundle of mobile games. Netflix can probably get away with including a few basic mobile games as long as they don’t have microtransactions, but this is another Catch-22 - if you’re successful, you’re out of policy, if not, who cares. Alternatively, the Netflix app could launch users into HTML5-based games via an in-app browser. However, these games are highly limited in functionality as they can’t access device drives using native APIs, and Apple cuts many off altogether. Another option could be to provide Netflix users with free access to paid iOS games, or free perks in said games, by logging into these titles using their Netflix ID. This complies with Apple’s bundling policies, allows Netflix to offload backend technology to individual game makers and iOS’s multiplayer services, and would even allow the company to have a “Games Included With Your Netflix Subscription” page in its standard video app. This isn’t a terrible solution, but it’s not a great one as it involves disintermediation by Apple (users would still download each game via the App Store and access the titles via iOS) and is probably a harder/less intuitive way for audiences to discover games compared to the App Store and standard marketing channels. This approach also means that Netflix would need to share 30% of all in-game purchases (i.e. microtransactions) with Apple, and allow Apple to bill Netflix’s customers directly. This is a big deal. In 2018, Netflix stopped supporting iOS based payments altogether, having decided that while the App Store made it easier for subscribers to sign-up, this didn’t justify handing over 15-30% of monthly ARPU to Apple. Netflix also knew that the following year, Apple would be launching its own competing SVOD service, Apple TV+ (which is natively integrated into iOS, advertised inside the iOS settings application, and pays a 15-30% commission to its sister division). It’s even possible that Apple would use Netflix’s game-based return to App Store-based billing to force Netflix to offer IAP for its streaming service as well. After all, Apple could argue that selectively supporting IAP is a bad and confusing user experience. Regardless, Apple doesn’t need to make a good argument. As The Verge wrote in 2020 following Apples whipsaw policy changes for cloud gaming, “Arguing over whether Apple’s guidelines did or didn’t include a thing is kind of pointless, though, because Apple has ultimate authority. The company can interpret the guidelines however it chooses, enforce them when it wants, and change them at will.”

On PC and Mac, Netflix can essentially do whatever it wants from a release perspective. Still, the prospects (at least in aggregation) seem slight. In 2018, Epic Games launched its Epic Games Store around the highest grossing video gaming in history, Fortnite, and its 250MM+ user accounts. The company also spent hundreds of millions a year buying exclusive windows to forthcoming games, and later, spent even more in order to give users free copies of hit games such as Civilization V and Grand Theft Auto V. Despite this and other maneuvers (e.g. charging half the commission of market leader Steam), the viability of EGS remains in doubt three years later, with even internal forecasts suggesting it may lose money until the late 2020s. Publishers such as EA and Activision have tried to launch their own stores and platforms for years - and withheld substantial portions of catalogue to do so, including hit games such as Apex Legends and Call of Duty: Warzone - and found even less success.

Collectively, the above means that Netflix can make local installation work, but the experience is complex and highly variable by device. On PC, Netflix can operate a fully-fledged bundle of AAA and mobile games. On console, Netflix is just a regular publisher. On TVs, it’s nothing. On mobile, it can offer only basic casual titles inside its app, or redirect users to standalone (and mobile-only) titles that have some discount for Netflix subscribers.

A theoretical solution here would be to launch a cloud game streaming service. This would allow Netflix to skip consoles altogether, as all a TV would need to do is run a thin application or offer a web browser. In addition, even the lowest-end mobile device could run the most GPU-intensive game. In other words, Netflix could reach nearly every device it currently reaches and with a consistent catalogue.

However, there are a few impediments here. For example, most argue that cloud game streaming is not currently viable for most gamers due to the generally poor state of networking infrastructure and hardware not controlled by a cloud gaming platform (i.e. the Internet backbone, neighborhood copper, household and apartment routers). Two years ago, Xbox head Phil Spencer, who has the most aggressive cloud gaming strategy of any Western platform, told GameSpot, “I think this is years away from being a mainstream way people play. And I mean years, like years and years."

Related Essay: Cloud Gaming: Why It Matters And The Games It Will Create

Cloud game streaming is also incredibly costly and computationally intensive. This is why the leading players in the space today are those who operate the largest cloud computing platforms in the world, namely Microsoft, Google, and Amazon. Notably, Sony PlayStation even formed a partnership with Microsoft’s Azure division for cloud gaming; it’s difficult to imagine Netflix, which relies primarily on AWS for its cloud needs, would be able to build a cost effective and global network of data centers. And not only does Microsoft cloud gaming service benefit from Azure’s operating scale, it literally uses un-shelled Xboxes as servers. This provides Microsoft with substantial cost advantages and means that game publishers do not need to produce distinctive builds of their games to support Xbox’s cloud platform. Google’s Stadia, meanwhile, is built on bespoke Linux-based servers, and the need to partly re-tool games for this stack is partly why publishers haven’t leaned into the service. This creates a vicious cycle for Stadia - fewer games means fewer players, which means there’s no reason for a publisher to develop for Stadia.

Netflix was able to “crowbar” into the entertainment industry through technology because it pioneered streaming video at a time in which most households had the internet speeds, reliability and latency required to enjoy Netflix. In addition, many of these households considered Netflix’s offering to be better (if less comprehensive) than the alternative (i.e. Pay-TV). None of this is true today. Netflix is late to cloud gaming, the technology is not yet “better”, and Netflix’s content offering will be structurally inferior. This is why the market leaders in cloud game streaming today, namely Microsoft and Sony, offer cloud game streaming at no additional cost for those who subscribe to their game bundles. This further reduces the opportunity for disruption by a new entrant (Netflix, Google Stadia, Amazon Luna, et al).

Competition

While Netflix was first to aggregate rights in and produce original content for digital video, it’s very late to both when it comes to gaming.

Microsoft’s online player network, Xbox Live, has over 100MM digital subscribers across PC, Xbox and Minecraft. In 2017, Xbox launched Game Pass, a subscription gaming bundle widely considered the “Netflix of Games.” Today Game Pass has nearly 20MM subscribers, and earlier this year, Xbox added free cloud streaming to all Game Pass subscribers. This means that for $15 per month, gamers can play over $100 worth of modern AA and AAA games on nearly any device they own, from an old Xbox to a low-end Android or aging iPhone. Moreover, Microsoft’s offerings are backed by more than 15 first party studios, the third most popular AAA console, native integration into the most used PC operating system globally, and ownership of the second most popular virtual platform globally (Minecraft). And from a technical perspective, Microsoft operates what is probably the world’s most sophisticated cloud gaming stack and recently brought together its many disparate divisions to produce one of the most significant proto-Metaverse experiences in any industry.

Sony’s PlayStation division is less focused on digital subscription services, but it has been the most popular console globally for over 25 years, and over two thirds of revenues today are digital. It’s also important to highlight that PlayStation Plus (the platform’s social gaming network, which also includes several free games per month) has over 50MM subscribers, while PS Now (Sony’s game bundle + game streaming service) has 3MM+. Sony also boasts the strongest collection of exclusive first party studios in the industry (and which have likely produced more new, globally popular IP over the last twenty years than any other entertainment company).

Content (or Competition, Part II)

If we look beyond aggregation and towards independent content owners, similar challenges emerge. It took Hollywood over a decade to vertically integrate and launch their own D2C service. However, today’s major game developers and publishers are already years into building digital D2C offerings. This is because, as highlighted earlier in this piece, almost all games today are “D2C.” And a single title can build an ecosystem that sustains billions of hours of engagement per year and reaches tens or even a hundred-plus million users monthly. Several publishers, such as Ubisoft and EA, even operate their own subscription bundles. And of course, the major game makers are routinely hitting record metrics (i.e. revenue, time, players), too. They don’t need a hand.

Furthermore, the most valuable IP/titles in the gaming industry typically maximize revenue by maximizing distribution, rather than selling exclusivity. And so, while Game of Thrones creates and captures the most value by being exclusive to HBO, Fortnite would shed most of its value if it were Xbox-only. In fact, maximizing reach is so valuable that the biggest games are now free-to-play; selling their titles to All-You-Can-Eat subscription bundlers actually increases payment friction.

(Yes, console exclusives exist, but they’re predominantly single player; therefore, limiting reach doesn’t harm the social experience. The most popular single player games will sell at best 25MM copies in their lifetime, while the top social/multiplayer titles will have 20-165MM players daily).

All of this makes it harder to answer what additive role Netflix would play in the gaming ecosystem. The company thrived in streaming video because it provided consumers with a cheaper, easier, and better way to watch premium video, while also offering content owners a new revenue stream. In gaming, it has no expanded reach (probably less), no extant player networks, and no clear ability to attract exclusive content. If Netflix wants to buy non-exclusive licenses, publishers will happily oblige. But to do this sustainably, Netflix must do more than offer subscribers access to non-exclusive titles that can only be played on a sub-selection of possible devices, and with no net improvements.

M&A might seem like a good answer - Netflix gets valuable IP, can build a franchise flywheel, offer exclusive titles - but it’s not really a great fit, either. Let’s imagine, for example, Netflix buying Ubisoft for $10B (a +50% premium to its current market capitalization). Ubisoft’s best-selling titles, such as Assassin’s Creed, release every few years and sell up to 15MM copies at between $10-60 retail and drive roughly 30 hours of average playtime over their lifetime. In other words, Netflix would be diverting two thirds of an entire year’s programming budget in order to reach maybe 5% of its users and grow service usage by even less.

(For what it’s worth, even Nintendo’s best AAA titles, such as The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild and Super Mario Odyssey, peaked at fewer than 25MM units).

Netflix could make all of these titles free-to-play, and perhaps use Google’s whitelabel Stadia service to ensure every Netflix user can play them regardless of the device used. However, there’s no evidence to suggest that these are severe constraints to their play today (as Stadia showed). It’s also important to highlight this approach still requires customers to purchase some standalone equipment (e.g. a $60 controller, potentially a dedicated streaming device).

These problems aren’t really solved by larger M&A. Activision Blizzard (which would probably cost $100B to buy, with Netflix currently valued at $240B and having never bought a company valued over $100MM) has far more reach (Call of Duty has 100MM MAUs, Candy Crush has 300MM), engagement (over a billion hours per month) and IP. But if Netflix can’t expand their distribution (or even directly distribute them), nor operate or design them better, what’s the point?

Netflix could focus on developing in-house AAA/mobile titles, or buy exclusive rights to them. And from this strategy, Netflix has the chance at creating its own hits - and as mentioned above, these hits can sometimes be platform-sized. But here, Netflix must compete with the (frothy) venture capital system ecosystem, as well as highly capitalized and profitable gaming platforms, such as Xbox and Epic Games, which have never provided developers with more project financing or non-exclusive licensing deals than they do today. In addition, these alternatives provide developers with far greater upside and more relevant experience and capabilities, too.

Compare all of the above to what it would take for Netflix to launch an on demand audio service. The world doesn’t need “another Spotify”, but the core stack is relatively easy to establish as Netflix already has on-demand audio functionality (i.e. tied to its video) and a robust recommendations engine (obviously more work would be needed). Furthermore, audio doesn’t require complex social features or multiplayer live ops. And with a few billion in minimum guarantees, Netflix could acquire non-exclusive rights to nearly all music ever created. $300MM a year could then provide the company with an expansive slate of originals, too. The business model is also straightforward: sell for $10 per month and pay out $7.5 in content costs. Audio is an important competitor in the “leisure wars”, and I don’t mean to suggest Netflix could easily conquer it. However, gaming is far more threatening in reach, implications, and entry.

#3: What Netflix Seems to Be Doing

Despite Netflix’s famous aversion to distraction, and the aforementioned impediments, the company has decided it must solve for gaming.

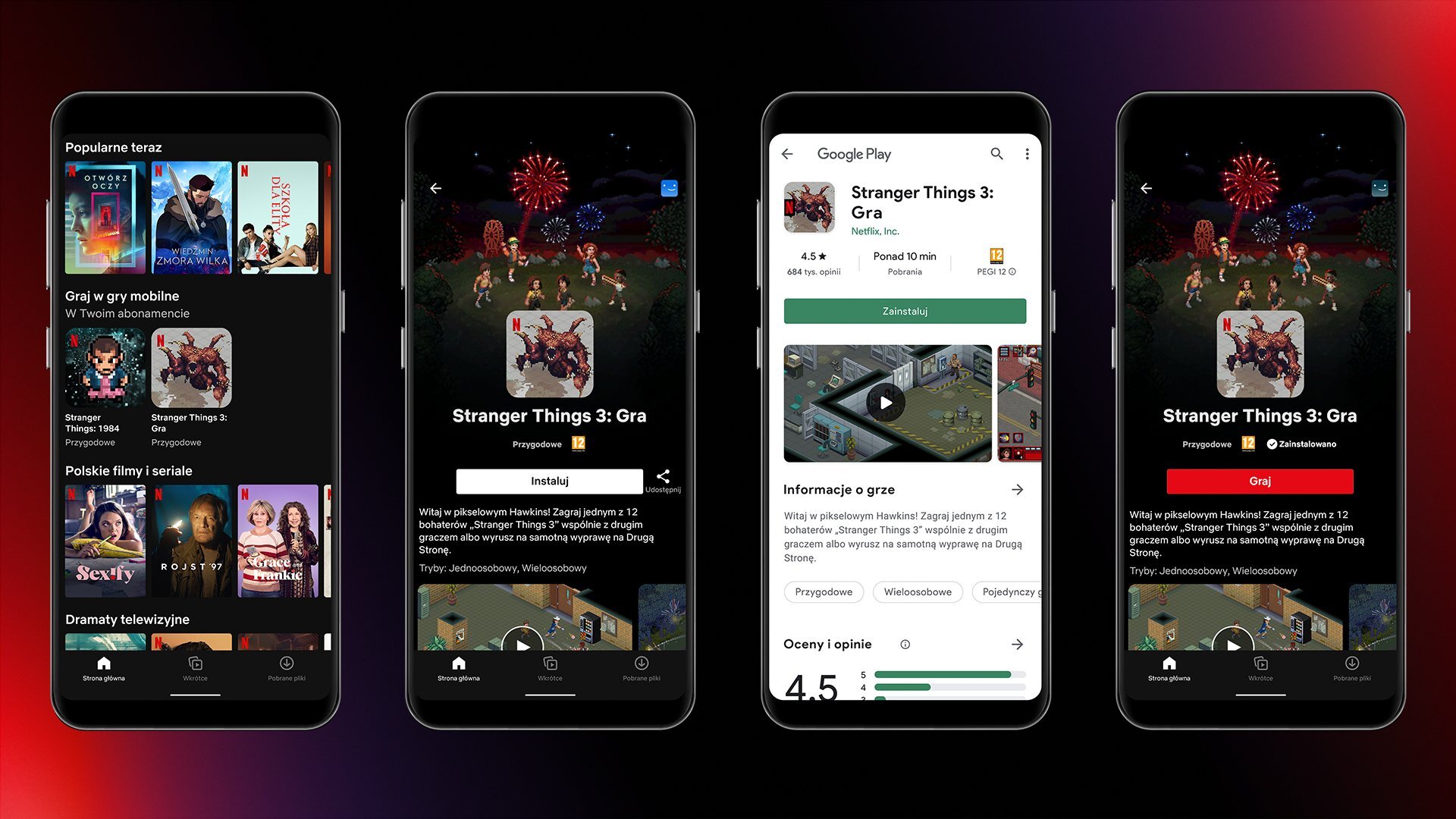

Based on press reports and public tests in Poland, Netflix’s gaming strategy seems to be focused on casual, single player, and mobile-focused titles. In addition, these titles are available at no additional fee for Netflix subscribers - and are only available to Netflix subscribers - and include no microtransactions or ads. There are some device limitations (e.g. a touch-based mobile game won’t work on your TV). These games can be discovered within the Netflix app, but require local installation. Specifically, a user is sent from the Netflix app into their device’s app store (i.e. Google Play), after which the game is installed at the OS level (e.g. as an icon on Android). Users can then open the game from Netflix, or from their device homescreen, but in either case the game runs as a standalone app. Notably, this means that the App Store has unilateral approval rights over the title (and also manages its updates and reviews) and integrates the title into its game services stack/network. And if Netflix does add microtransactions to these titles, the app stores will take a 30% cut.

From an offering perspective, this seems a lot like Apple Arcade, a $5 per month service from Apple that offers users access to a bundle of nearly 200 mobile games. None of these titles have micro-transactions, though some are multiplayer. Because Arcade is iOS-focused, it is limited to devices that run iOS apps.

Based on third party data services (e.g. SensorTower, which tracks downloads), Apple Arcade does not seem to be very popular. Most estimates suggest 5MM or fewer subscribers, which means the service is used by less than 0.5% of Apple’s 1.1B active iOS users.

We can also contrast the performance of Apple Arcade with Apple Music. Arcade costs half as much as Music and operates in a market four times larger. Music also has nearly an identical catalogue to market leader Spotify, which launched four years earlier in the United States and nine years earlier in select foreign markets, while Arcade, is almost entirely made up of exclusive content, was the first major mobile gaming bundle to launch on iOS, and due to iOS store policies, is essentially the only one operating today. Despite this, Apple Music has over 75MM users compared to Arcade’s 5MM.

Most telling, however, is Arcade’s churn. Roughly 20% of subscribers leave the service each month (implying an average tenure of only five months). This is three-and-a-half times the worst performing SVOD. In fact, Apple Arcade experiences more than twice the churn of HBO in the month after the finale of Game of Thrones… but every month! Note that Netflix’s churn is best in class by some margin.

Because Netflix’s service is free, it doesn’t face the same hurdle to usage or value as Apple Arcade. But it is also far harder to use than the latter service. Because Apple owns iOS, Arcade is actually allowed to bundle these games inside a single app and doesn’t require users to jump over to the App Store in order to install them. That’s a much better user experience. Netflix does benefit from the ability to drive discovery of its gaming catalogue via its application, but then again, Apple advertises Arcade within its operating system.

More broadly, it’s not clear that Netflix’s gaming strategy complies with Apple App Store policy (which may explain why the company’s tests in Poland are Android only). And if it is currently compliant, growth in its offering or resonance could make it non-compliant. Apple, for example, might decide that Netflix has become a bundle of a video service and gaming service, rather than a video service that has a few free games are perks. And then demand a cut of subscription fees.

Putting that aside, the struggles of Apple Arcade make it clear that Netflix’s gaming offering can only thrive if it includes great content. And it will be hard for the company to get truly great games.

One thing Netflix has highlighted is that its titles won’t have lootboxes, gacha mechanics, or any microtransactions. It has argued that this will attract both players and developers, despite the challenges I listed earlier. And certainly, consumers don’t actively like these features, nor do most game makers get excited about them.

Despite this, it’s not clear that the best games are worsened by micro-transactions. Fortnite is probably better because there’s scarcity of cosmetic purchases (creating individuality of representation/identity). And there is a relatively low ceiling on how many cosmetics a given user will buy specifically because they’re about representation. Fortnite does have a gated battle pass that’s required for some in-game activities, but it doesn’t disadvantage players who don’t purchase it. In fact, players who complete the battle pass collect 1,000 free V-Bucks, even though the pass costs 950 V-Bucks.

Not all games have Fortnite’s healthy approach to monetization, but the point is that the existence of microtransactions isn’t what makes a game “good” or “bad.” Instead, it is how they’re implemented and why (much like violence in a TV series). The problem with Candy Crush isn’t that you have to pay for more lives or perks, it’s that some pay thousands a month (literally). If King Digital wanted to, the title could just have a $250 monthly unlimited tier.

Note, too, that Apple also made the “no ads, no micro-transactions” argument for Apple Arcade. It hasn’t led to better games from the perspective of players. In fact, it probably makes acquiring high quality games even harder. Subscriptions already cap the upside economics for a developer, while also partly disintermediating them from the end player. By rejecting microtransactions, Apple and Netflix are eliminating the possibility of all tail revenues (or direct revenue sharing). And given that games, unlike individual films and TV series, do not need to be aggregated in the first place, this makes a tough sell even harder.

All of this means Netflix will have to draw primarily on novice talent and work-for-hire shops, as well as internal studios, to build up its content offering. This doesn’t mean a hit is impossible, only that it’s less likely and will take longer. It’s particularly hard to form new game studios, as it can take 3-5 years to release a single AA or AAA title (on a comparative basis, a well-backed TV studio could produce several titles in half the time). Furthermore, hit rates in the gaming industry have never been as low as they are today. Mobile game submissions to the App Store are down 75% since the mid-2010s, while the world’s largest AAA studios are struggling to create new franchises (even when The Avengers are assembled). Today, every single studio at Activision supports the Call of Duty franchise. And Netflix is still learning how to make a TV or film series a decade after greenlighting House of Cards, which was made by outside production company MRC (Netflix’s hit rate with original series is well below that of competing streamers, while Hastings has admitted the company has a “ways to go” when it comes to producing franchises like the rest of Hollywood).

And as mentioned above, Netflix probably faces a low ceiling in terms of how many games it can launch within its app while still complying with Apple’s App Store rules. If it wants to offer many games, especially good games, it will have to take a “Single Sign On” approach whereby users download standalone apps that take their Netflix ID. This means Netflix’s gaming network/bundle will still be free to Netflix subscribers (in contrast to the $5 Apple Arcade), but it means disintermediation by Apple, additional access friction, and asking users to install a field of apps. Imagine, for example, if watching Netflix required users to download a distinct iOS app that would be used to access every show or movie.

It’s unlikely that Netflix thinks its current games strategy will be a smash hit. That’s not to say that the impact will be negligible. Netflix has 210MM subscriptions with 3.5 profiles per subscription, and thus over 700MM monthly-to-daily users. No one, save for Apple and Google, reaches more players. This is one of the primary reasons Netflix’s embrace of gaming felt so inevitable. It’s easy to imagine millions playing a Match-3 game branded on The Crown within the Netflix app simply because it’s there - even if it’s worse than other Match-3s. And this will drive incremental engagement for Netflix, some of which will occur in places and at times in which Netflix is not practical today or where it typically loses to mobile games (e.g. standing in the tube). This incremental engagement will have a non-zero impact on churn, while also helping to fortify the company’s IP. This is all good.

#4: Where This Might Be Going and When

The cynical take on the above is that it’s a gimmick (or worse, intended to distract from escalating competition for subscribers and good content). It’s more likely that Netflix’s gaming strategy is long-considered and long-term oriented.

Consider Netflix’s trajectory in streaming video:

1997: Netflix launches as a DVD-by-mail business

2001: Netflix begins developing its streaming video stack

2007: Netflix launches streaming video as a free-bundled service within its DVD service

2009: Netflix introduces its Originals brand internationally

2010: Netflix’s streaming service becomes a standalone service from its DVD service

2011: Netflix commissions its first Original Series, House of Cards (though it does not buy all rights to the series)

2013: Netflix airs its first commissioned Original Series House of Cards

2016: Netflix airs its first internally developed blockbuster, Stranger Things

2017: Netflix Originals exceed half of new spending

2018: Netflix releases its first interactive video Original, Bandersnatch

And if we’ve learned anything over the past thirty years of “Big Tech” in gaming, it’s that sudden, dramatic, and/or expensive forays are likely to be a mistake.

Today, Microsoft has a thriving and strategically valuable business. But Xbox launched twenty years ago and is believed to have been a cumulative money loser for more than a decade. Reports suggest that as late as 2018, Microsoft was considering offloading the division. Investors now value Minecraft, which Microsoft bought for $2.5B in 2014, on par with the entire Xbox division.

Amazon has spent billions building Amazon Game Studios, only to face years of delays, budgetary overruns, cancellations and bombs. No hit games have yet been released. Amazon also bought and invested hundreds of millions of dollars into a proprietary game engine, Lumberyard, but almost no developers adopted it (and none produced a hit). Earlier this year, Amazon handed the engine over to Linux. In 2021, the company also released a cloud gaming service, though almost no one knows it exists, let alone buys it. The company’s most successful gaming business, Twitch, was acquired in 2014 and is reportedly years behind revenue forecasts according to The Information.

Google’s ambitious Stadia initiative, which was widely described as “destined for the Google Graveyard,” was scaled back and partly shuttered less than 18 months after its launch. Not only did this retreat occur faster than anticipated, but it occurred in the middle of a pandemic that lifted the entire gaming category and prompted Google’s primarily competitors, such as Microsoft and Facebook, to publicly commit to building the “Metaverse.”

In this context, Netflix’s current strategy is probably right. The focus on lightly casual, single-player mobile games minimizes the cost and size of individual games, as well as the backend technology needed (e.g. social accounts system, live services). It also simplifies delivery (i.e. local install versus cloud) and reduces the likelihood of conflict with a given platform (e.g. iOS or PlayStation). By bundling titles inside the Netflix app and skipping microtransactions, the creative/quality hurdle is probably lowered, too.

Yes, all of the above means a more modest future for Netflix in gaming in the years to come (just as streaming video once was). However, it also provides more time to build up its internal capabilities (e.g. tech, creative, live services, multiplayer/social) and gaming brand (for both developers and players), while offering the (tail) chance at producing a sleeper hit and for regulatory changes to make it easier to distribute and monetize games on third party devices and platforms. In other words, Netflix’s optionality grows. This is the most important point. And is reiterated by Netflix’s hiring of Mike Verdu as game lead (who was previously the VP in charge of Facebook's AR/VR gaming division, an SVP of EA’s mobile division, an SVP and CCO at Zynga, and a GM in EA’s AAA portfolio.

Gaming is unique in the entertainment industry in that it experiences constant technological changes that lead to additive, not disruptive growth. This is because the addition of mobile gaming, as an example, didn’t involve moving content from a console to a handheld, but instead made it easier and cheaper for more people to game in more places, while also enabling new interaction models (i.e. touch). Arcades have been shockingly resilient over the past several decades because consoles offer very different experiences - not just in location, but technology. For example, consoles made “saving” practical, which meant a game could have richer, longer, story-based narratives, and develop more nuanced skillsets as they progressed dozens of hours into the title.

The differences in different gaming technologies meant that whoever led in one era, from either a device or content perspective, usually didn’t lead in the next. Atari and Namco, both leaders in the arcade era, didn’t lead in consoles. That’s Nintendo and Sony, as well as publishers such as Square Enix and Ubisoft. None of these companies have much strength (or even presence) in PC, nor in mobile (where the PC leaders are also weak). And when we look at UGC platforms and virtual worlds, it’s no surprise that new giants, such as Roblox and Minecraft, are at the forefront.

Gaming, or I should say interactive, has never been as diverse or fast changing as it is today. After several false starts, it’s clear the VR gaming ecosystem is now attracting mainstream gamers and developers alike. AR has been growing for years, and the technologies that support and advance these experiences (e.g. ultra-wideband RADAR chips, LIDAR cameras, BLE) are being rapidly deployed in consumer-grade devices.

As much as Netflix has disrupted entertainment, most of the changes in premium video have been delivery-related: on-demand viewing, ad-free experiences, binge releases, recommendation-based discovery, auto-play next and skip credits, etc. Bandersnatch was different and praiseworthy, but still a linear string of pixels that required little-to-no user involvement (after ten seconds, the show would literally pick for you) and wasn’t fundamentally enriched by it. Almost nothing we watch on our multi-sensor portable “supercomputers” couldn’t be watched on a 1960s CRT TV. The color and resolution would be worse, sure, but it would still be the same Stranger Things or Game of Thrones.

“I don’t want to make a prediction for Netflix, but I am certain within the next two-to-three years, you’ll be able to freeze the frame, put on a set of VR or AR glasses or look through your phone, then walk into the scene and go anywhere. Let’s say they produce a Godfather movie and it’s in 1960 New York. The traffic will be there, the shop keeps will be there. You’ll be able to wander around that world and interact. Not just by yourself, but with your friends, and their friends. And it can be while the film was taking place, or freezing it just looking at the way it looks right now. Or be completely independent of the film itself. The world will be real.” - John Riccitiello, CEO, Unity Technologies (2020)

As “games” like Fortnite expand into more “non-gaming” experiences, more franchises pursue cross/transmedia storytelling, and virtual production (which primarily uses game engines for live 3D rendering) proliferates, video, as a category, will need to embrace interactivity. Not all video, but some. It’s somewhat remarkable, for example, that we haven’t seen horror series that leverage eye tracking to supercharge a fright. Or smart home devices to immerse and enrich suspense. The biggest leap in audience interactivity in video entertainment was twenty years ago with Pop Idol! And all this interaction involved was asynchronous telephone voting. Genvid (which recently raised $113MM and added 18-year Netflix veteran and long-time Head of Original Series Cindy Holland as an advisor) is building “Massively Interactive Live Event” programming that allows millions of users to affect a narrative in real-time by voting, solving puzzles, and involving themselves in the action. What if, for example, the audience powered mission control in Cabin in the Woods? (The below is a concept trailer).

How all of this plays out is hard to predict. But what’s certain is that interactivity will continue to grow its share of leisure time and there will be new winners.

To thrive in the “Leisure Wars,” Netflix needs to start building, and testing, and creating in interactivity. It need not rush, but it cannot just wait. Hastings recognizes this, and so work is underway. And for what it’s worth, Netflix’s largest traditional competitor, Disney, has sworn off gaming.

Matthew Ball (@ballmatthew)