The Founding of Epic Games and How Its First (And Accidental) Game Became “Unreal Engine 0” and Now Defines Fortnite

To commemorate the release of the fully revised and updated edition to my 2022 book, THE METAVERSE: BUILDING THE SPATIAL INTERNET, I wanted to share one of my favorite additions. As roughly 70% of the book is new, there are many additions to draw from – but I love this section for a few reasons. First, it reflects the book’s expanded focus on the people, companies, philosophies, and histories behind the Metaverse. Second, it reminds readers that Epic Games has been working towards the “Metaverse” for four decades now (since the start of its first game, in fact)! Third, it’s a testament to the unpredictability of innovation and how “Unreal Engine 0” presaged sandbox-style gaming, UGC, and modding, as well as Fortnite’s UEFN overall. Fourth, I fondly remember playing ZZT on my PC as a kid.

Excerpt from Chapter 3:

Epic had been founded by Tim Sweeney in 1991, the same year as id software, but the company initially focused on 2D games, such as ZZT, Jazz Jackrabbit, and Jill of the Jungle. According to Sweeney, the release of “Wolfenstein and DOOM… changed everything. The titans were busy building huge 2D games and Epic took a huge leap of faith on 3D.” In the months after Wolfenstein’s release, one of id’s business leads, Mark Rein, joined Sweeney as a co-founder, and by 1995, Epic had merged all of its smaller teams working on 2D games into one focused on a true 3D game—1998’s Unreal.

Like Quake, Unreal was a “true 3D” sci-fi multiplayer shooter and a near instant hit. It achieved an 89% average review on GameRankings (the predecessor to Metacritic), was the 14th-best-selling PC game of the year, sold 1.5 million units by its fourth anniversary, and led to a direct sequel in 2003, as well as four multiplayer-focused spin-offs (Unreal Tournament in 1999, Unreal Tournament 2003, Unreal Tournament 2004, and Unreal Tournament 3 in 2007). As discussed at the start of this chapter, Unreal was also Epic’s first effort to build a “proto-Metaverse” of sorts, though it was limited to “text chat” and “300-polygon strangers.” Despite the success of the game, Unreal’s greatest legacy was the engine technology that powered it.

Unreal had cost about $3 million to produce ($6 million in 2024 dollars), most of which was spent on its engine, dubbed “Unreal Engine,” rather than gameplay or artwork. Most game developers at the time could not afford such investments and those that could weren’t guaranteed an equally useful result, either. And so in 1996, two years before Unreal was even released to the public, Tim Sweeney bet he could build a business around its engine. Though licensing UE meant aiding Epic’s gamemaker rivals, some of whom produced directly competitive titles such as Duke Nukem, it netted the company $250,000– $350,000 in upfront payments and 5%–7% in royalties from the sale of these titles. It also enabled Epic to further its investment in UE and to benefit from the R&D of its licensees, too. In September of 1998, Sweeney told Maximum PC: “The big goal with the Unreal technology all along was to build up a base of code that could be extended and improved through many generations of games.”

By 1996, id had begun selectively licensing its Quake Engine, too—and saw early success when Valve produced its 1998 blockbuster title Half-Life using a modified version of the Quake Engine— but most developers opted to build on UE. And while Unreal was inspired by the early 3D games of id Software, the Unreal Engine’s source of inspiration was Epic’s very first game, the 2D puzzler ZZT (which didn’t stand for anything, but ensured the title was listed last in a file directory and thus easy to find).

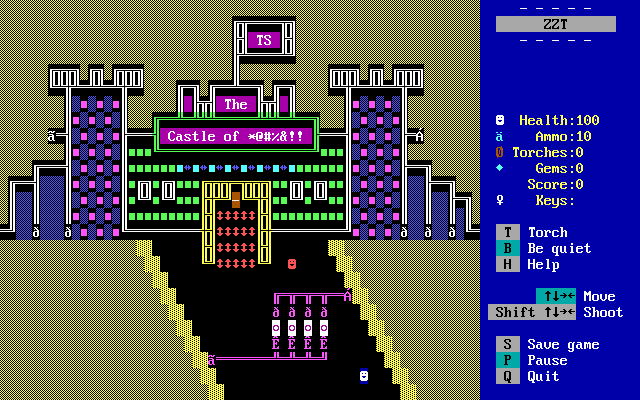

In 1989, Sweeney had begun building a text editor, because he disliked those available on PCs at the time. Eventually, he transformed his nascent text editor’s cursor into a smiley face, then designed and inserted other characters into the application, followed by labyrinth-like walls, the ability to collect ammo and shoot enemies, discover keys used to unlock doors, and so on, until he had produced a colorful 2D action-adventure puzzle game. After encouragement from friends, Sweeney decided to release ZZT publicly in January 1991. By November, the 20-year-old Sweeney was generating over $3,000 in monthly sales from ZZT (equivalent to $6,700 in 2024 prices). Less than a year later, monthly sales exceeded $25,000 ($58,000).

Due to its origins as a text editor, ZZT’s “graphics” were actually just made up of the 256 characters that constituted the ASCII standard, each of which was one byte in size, and spanned the numbers 0– 9, lower and uppercase versions of all 26 English letters, various mathematical symbols such as π and + as well as select punctuation like !, shading blocks like ▒ or ▓, and other signs like ↑ and ▲. While ASCII had been popular in the 1960s and 1970s, it had largely fallen out of style as computers gained the ability to render individual pixels, which led to the rise of more specialized in-game art. As such, ZZT’s visuals were inferior to those of titles as old as 1978’s Space Invaders or other maze-focused games like Pac-Man— and the title fell particularly short of other 1991 releases, such as Sonic the Hedgehog and The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past. Yet ZZT’s technical foundations provided the title with a key advantage.

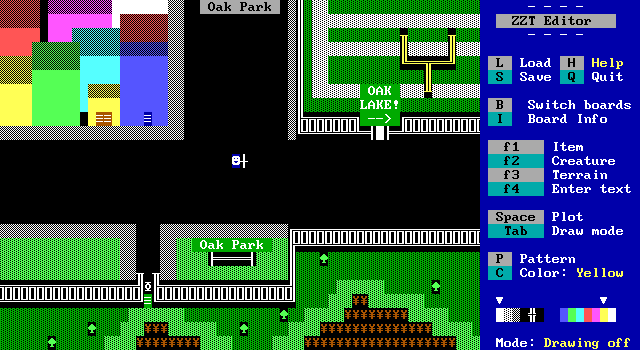

In addition to its fun and intuitive gameplay, ZZT thrived because of Sweeney’s decision to include a customized version of the very software he used to make it, thus allowing users to build their own levels using his ZZT-OOP scripting language. ZZT was not the first video game to support or encourage “user-generated content”— MUDs were based on that very premise and dedicated game-creation software had been released throughout the 1980s for consoles such as the Commodore 64 or Atari ST. However, ZZT’s origins as an editing program and Sweeney’s interest in such functionality meant that ZZT’s tools were far easier to use than those afforded by other titles. In contrast with other game creators, ZZT was also downloaded over the internet, rather than purchased via cartridge or disk. Accordingly, users could easily (and freely) share their mazes with other users online, which helped grow awareness of ZZT while also deepening its gameplay.

Eventually, Sweeney announced a contest in which users could submit their mazes to his company, then known as Potomac Computer Systems. The winning entries were then packaged in the 1992 sequels Best of ZZT and ZZT’s Revenge, with their creators receiving gift certificates and/or honorable mentions in the game’s credits (six creators even won jobs at the newly renamed Epic MegaGames).

Sweeney credits ZZT with convincing him to start a gaming company and setting its “core philosophy. . . . We both build games ourselves and we share all the results of our work with the world to build their own games.” And as the company shifted its focus to 3D in the mid-1990s, Sweeney aspired to produce a 3D engine that was as easy to use as it was powerful, thereby enabling creative teams to spend more of their time making a game, not building the tools needed to do so, or learning how to use those same tools. To Sweeney, ZZT was “sort of a prototype Unreal Engine 0.”

The development of easy-to-use, cross-company tools such as UE are key to establishing the Metaverse. Previously, building a virtual world required a developer/creator to acquire deep technical expertise and design their own tools, just like Epic Games or id Software, or build within a platform, such as Second Life or ZZT. The former approach constrained how many virtual worlds were created, and led to technical fragmentation that made interoperation difficult. The latter approach, meanwhile, produced networks within an application, rather than a network of applications.

In the quarter century since its debut, the Unreal Engine (now “Unreal Engine 5”) has become the most widely used “high-fidelity” engine for 3D games and its usage has expanded into architecture, healthcare, automotive, and countless other industries and use cases. What’s more, Epic has taken a remarkable, yet familiar bet. Barely a year after Fortnite’s debut in 2017, the battle royale shooter grossed a reported $5 billion (net to Epic) and $7 billion (in player spending), more than doubling the prior record for a game’s revenue over a 12-month period. Despite this unprecedented success, Epic believed Fortnite could be more than just a battle royale game – or even shooter game. On December 6, 2018, the company launched Fortnite Creative, a UGC-sandbox platform that enabled anyone to build their own games inside Fortnite and using the Unreal Engine. By 2022, half of Fortnite playtime was in Creative Mode, and in 2023, Epic announced that up to 40% of Fortnite revenue would be paid out to creators and that its marquee battle royale would be just one of tens of thousands of discoverable tiles on the Fortnite landing page.

For more, please grab a copy of “The Metaverse: Building the Spatial Internet” available now at a booksellers everywhere, including Amazon, Apple, Barnes & Noble, Bookshop.